One hundred years ago this month, Bertrand Russell – a philosopher, mathematician and pacifist, who would become one of the best-known public intellectuals of the 20thcentury – entered the stony gates of London’s Brixton Prison.

A fierce opponent of the Great War still raging in France and Belgium, Russell had received a six-month sentence for violating Britain’s Defence of the Realm Act, convicted for a comment he wrote in the newspaper of the No-Conscription Fellowship – an anti-war organization that provided support for conscientious objectors, and in which Russell was a central figure.

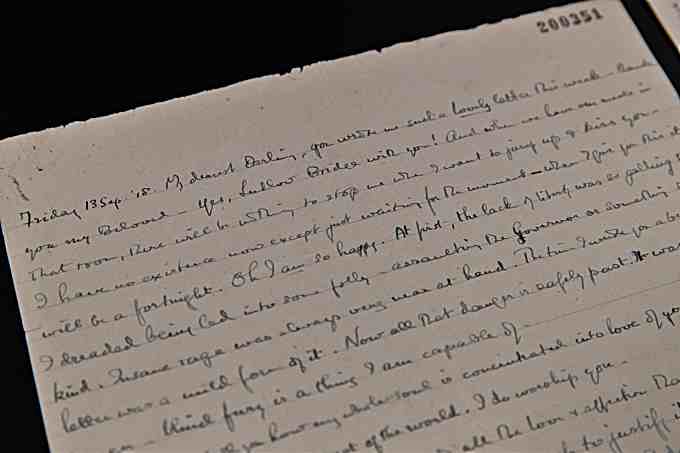

From the confines of his cell at Brixton, Russell – already a renowned philosopher and author with connections to some of the most famous and infamous figures of the day – focussed his intellect and emotions on writing, producing philosophical works, and penning scores of letters to those in his inner circle.

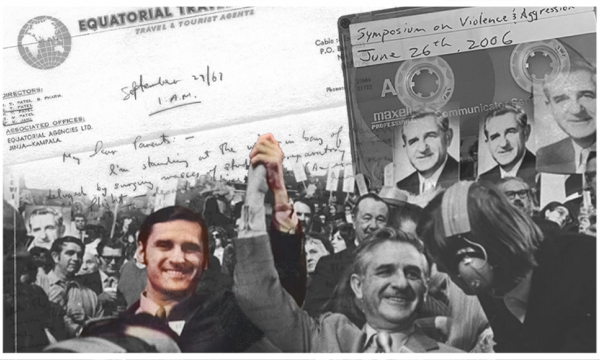

Now, for the first time, Russell’s prison letters – part of McMaster’s Bertrand Russell Archives– are being made available online through a new digitization projectdeveloped by the Bertrand Russell Research Centre. Complete with detailed annotations and fully searchable text, the project is providing scholars from around the world with access to these rarely seen materials.

“The letters reveal the private thoughts of one of the 20thcentury’s most public figures and provide an interesting window on Russell’s inner life,” says Andrew Bone, Senior Research Associate at McMaster’s Bertrand Russell Research Centre who is leading the digitization project, along with Nick Griffin, Canada Research Chair in Philosophy and director of the Bertrand Russell Research Centre, Kenneth Blackwell, the Russell Archivist Emeritus, and Sheila Turcon, a former McMaster archivist, and Russell scholar.

The collection contains 104 letters, a number of which are written on prison stationery and initialed by Brixton’s governor – the only correspondence Russell was officially allowed. But the majority of the letters were written in secret and smuggled out of Brixton by Russell’s friends, concealed between the uncut pages of books.

“Russell’s ingenuity makes our enterprise a lot more interesting because otherwise we would have been left with just the weekly form letter in which Russell tried to transact as much business as possible,” explains Bone. “But the unofficial ones – the hidden ones – are often much more interesting.”

Though deeply involved in Britain’s peace movement in the years before his imprisonment, the letters contain comparatively little about Russell’s anti-war activities. But they provide unique insight into his personal relationships, particularly those with his then lover Lady Constance Malleson (known as ‘Colette’) and his former lover, aristocrat and socialite Lady Ottoline Morrell.

Morrell, along with Russell, was a member of the famed Bloomsbury Group which included some of Britain’s most famous artists, thinkers and writers. Her home, Garsington Manor, served as a refuge for many of these figures including pacifists and literary celebrities such as D.H. Lawrence, and T.S. Eliot, many of whom are referenced in the letters.

“Ottoline was like the star around which orbited many interesting people in English intellectual and cultural life,” explains Bone. “She wrote about her guests and Russell inquired back. So it was as if he was vicariously involved with the Bloomsbury Group’s activities from his prison cell.”

At first, Russell viewed his relatively comfortable and privileged confinement as a “first-division” inmate as a respite, an opportunity to focus on his philosophical writing and to distance himself from the No-Conscription Fellowship with whose infighting he had become disenchanted. But as the weeks and months wore on, Bone says, the letters reveal he grew increasingly listless and felt isolated, particularly from Colette.

“His letters to Colette are highly romantic,” says Bone, adding that some of them were even written in French to disguise their contents. “His affair with Colette was incredibly intense and Russell is exceedingly jealous of what she may or may not be doing – he’s tortured by this and he emotes that extremely graphically in many of these letters.”

The collection also contains letters to others who were close to Russell, notably his brother, Frank, the second Earl Russell; and his unofficial secretary, Gladys Rinder – a member of the No-Conscription Fellowship who was entrusted with distributing both Russell’s illicit correspondence, as well as the messages to pacifists, philosophers and other intellectuals contained in his authorized letters. As well, the collection includes his routine correspondence with editors, publishers and the prison authorities.

All the letters written by Russell during his time at Brixton will be made available online over the next few months and released on the days on which they were written.

Follow #@MacResCollson Twitter for links to each letter as they become available

“Hopefully, putting these letters online will generate interest in the collection, and in the Bertrand Russell Archives as well. I just hope they’ll be read, absorbed and enjoyed by Russell scholars and by those who are new to Russell as well,” he says.

There are about 40,000 letters by Russell in McMaster’s Bertrand Russell Archives. Bone says the Bertrand Russell Research Centre hopes the Brixton Letters Project will become the foundation for other digital editions of letters within the archives.

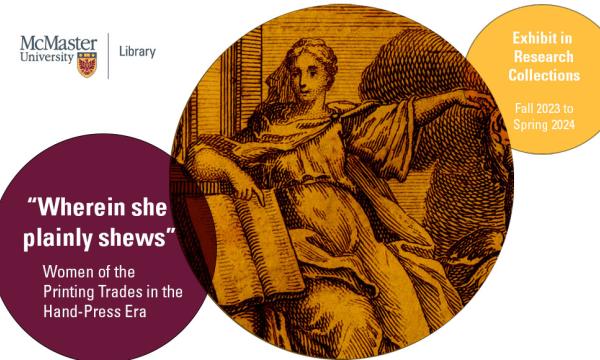

2018 marks the 50thAnniversary of McMaster’s acquisition of the Bertrand Russell Archives, the university’s largest research collection. The Library will celebrate the opening the Bertrand Russell Archives and Research Centre, the new home of the Russell Archives, located at 88 Forsyth Street N. this June.

Read more about the 50thanniversary of McMaster’s Bertrand Russell Archives