In the 1850s, southern Ontario looked vastly different from the urban expanse we see today.

Instead of sprawling subdivisions, small villages with names like Sand Hill, Charles Town and Westervelt’s Corners dotted the landscape. Instead of high-rises and big-box stores, churches, one-room schoolhouses, and family businesses, like the Orangeville Tannery and R. Chisholm & Co. Dry Goods, made up the familiar scenery of everyday life.

Though most of these landmarks have long since vanished, a newly preserved rare map is providing a snapshot of what life in the GTA looked like 160 years ago.

Using new, experimental techniques, McMaster University Library conservators have painstakingly restored a large-scale 1859 wall map of the County of Peel produced by famed map publisher George Tremaine.

The conservation project was funded by a donation from McMaster graduate Elaine Campbell ’76, in memory of her parents. The Library directed her gift toward the project to honour Campbell’s family connection to the map, a connection staff discovered when Campbell visited the Lloyd Reeds Map Collection.

“At the time of my visit, I was shown one of the maps that the conservators might work on,” says Campbell, who graduated with a degree in Geography and whose professional career was spent in libraries and research. “As it was unrolled, I saw that it was the 1859 Tremaine map of Peel County. My reaction was immediate and emotional.”

“I asked how the staff knew I had a connection to Peel County,” she continues. “They had no idea that my maternal grandfather's family started settling there in the 1820s. I found the names of a great-great-great grandfather, two great-great grandfathers and numerous other relatives.

So, the map found me.”

History meets science

Campbell’s gift was intended to not only preserve the map for use by researchers, but also to provide conservators with an opportunity to experiment with new techniques that could inform the preservation of Tremaine maps in the future.

Produced between 1856 and 1888, Tremaine’s county maps contain a wealth of period details that provide unique insight into life in 19th-century Ontario.

“The maps include the usual things like roads, towns, and property lines but they also contain little vignettes – sketches of churches, businesses and other important public buildings from the time, many of which no longer exist,” says Gord Beck, McMaster’s map specialist.

“If you were wealthy enough, you could even pay to have a picture of your home or estate included,” adds Beck. “So, they became a status symbol as well as a map.”

Because of their detail and accuracy, Tremaine’s maps were widely used and became a fixture on the walls of government buildings and private companies of the era.

Though a large number were produced, Beck says few have survived and those that have are damaged as a result of improper storage, staining, and a host of other issues common to maps from this period.

McMaster’s map was no exception.

Carefully preserving ‘nightmare paper’

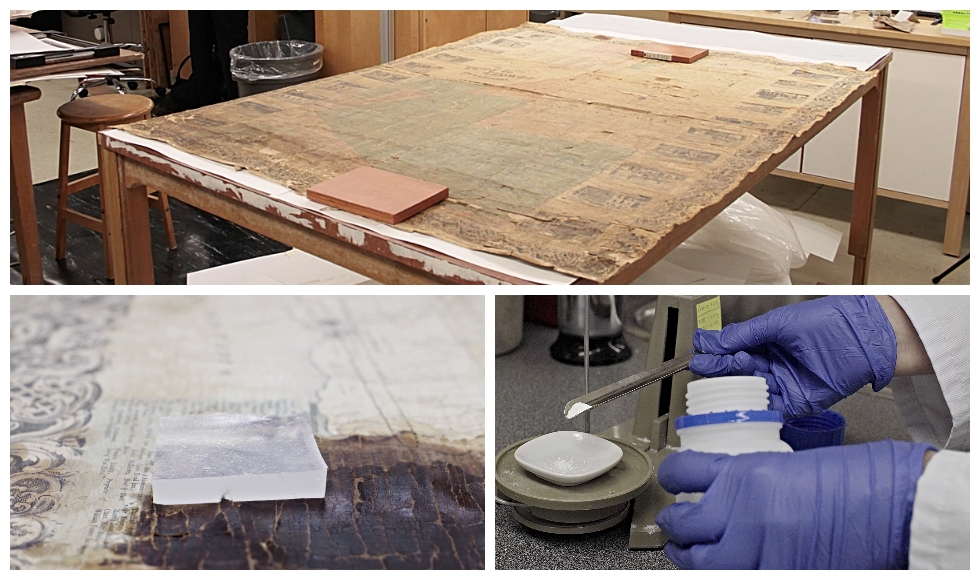

“We couldn’t pull the map off the shelf without pieces falling off,” says conservator Julie Niven, who led the preservation project. “Also, the stains and cracking made the map nearly impossible to read in some places – there was no way it could be used by researchers.”

She says the poor condition of the map was caused by a few key factors, starting with the paper it was printed on.

“The map is on wood pulp paper, which is a nightmare paper for conservators,” says Niven who explains that this type of paper, made during an experimental period in paper making, has a high lignin content and was made using a variety of chemical processes, often resulting in an acidic paper that is susceptible to crumbling.

The map was also deeply stained in several places and soiled with insect excrement known as “fly specks.” Plus, a layer of varnish originally intended to protect the map had oxidized over time, leading to discolouration, cracking and flaking.

Working in McMaster University Library’s Preservation Lab – one of the few facilities of its kind in Canada – Niven looked for ways to combat these issues by experimenting with a range of new conservation techniques.

“In conservation, experimentation is inevitable because every item is different,” says Niven “You never know what will work until you get your hands in there.”

To lessen the staining, she created and applied squares of gellan gel, a polymer which, over repeated applications, absorbed the stains, significantly reducing the map’s soiled appearance and making it possible to read the writing beneath.

Niven was also able to reinforce the crumbling paper by adhering the map to a Japanese paper backing, preventing further disintegration and allowing the map to be handled without damaging it.

But the varnish, says Niven, posed a much bigger problem.

“Removing the varnish was the challenge,” she says. “Varnishes from this period vary widely in their formulations, whether they come from manufacturers or people making their own, so it’s difficult to know what’s actually in them.”

After much experimentation, Niven was able to remove the varnish using a citrate salt cleaning solution to reveal the original paper beneath.

A record of every farm in Peel

The finished result is a legible, structurally sound historical artifact that can now be digitized and used by scholars and the public.

“It’s really an incredible resource,” says Beck “It shows the name of every farm and landowner in Peel County at the time. It includes little black squares where the farmhouse was, and circles that show the location of the orchard, as well as churches and cemeteries that may no longer be there.”

These are all things that can play an important part in environmental assessments, genealogy, or for archaeological purposes.”

McMaster University Librarian Vivian Lewis says the conservation of the County Map of Peel is a culturally significant project that will serve the public and scholars for years to come – and one that would not have been possible without Campbell’s support.

“For many years, this rich historical resource couldn’t be used without risking further damage,” says Lewis. “Now, thanks to Elaine’s generosity, not only is this map, and the valuable information it contains, visible to researchers, but the conservation techniques developed in the process can be used for future preservation projects, benefitting McMaster and other cultural and educational institutions undertaking this important conservation work.”

As a next step in making the County Map of Peel available to potential users, the Library plans to digitize the map and share it publicly through McMaster’s Digital Archive.