References and Recommended Reading

The Canadian Encyclopedia

Thomson, Don W. Men and Meridians: the history of surveying and mapping in Canada. volume 2, 1867-1917. Queens Printer, 1967.

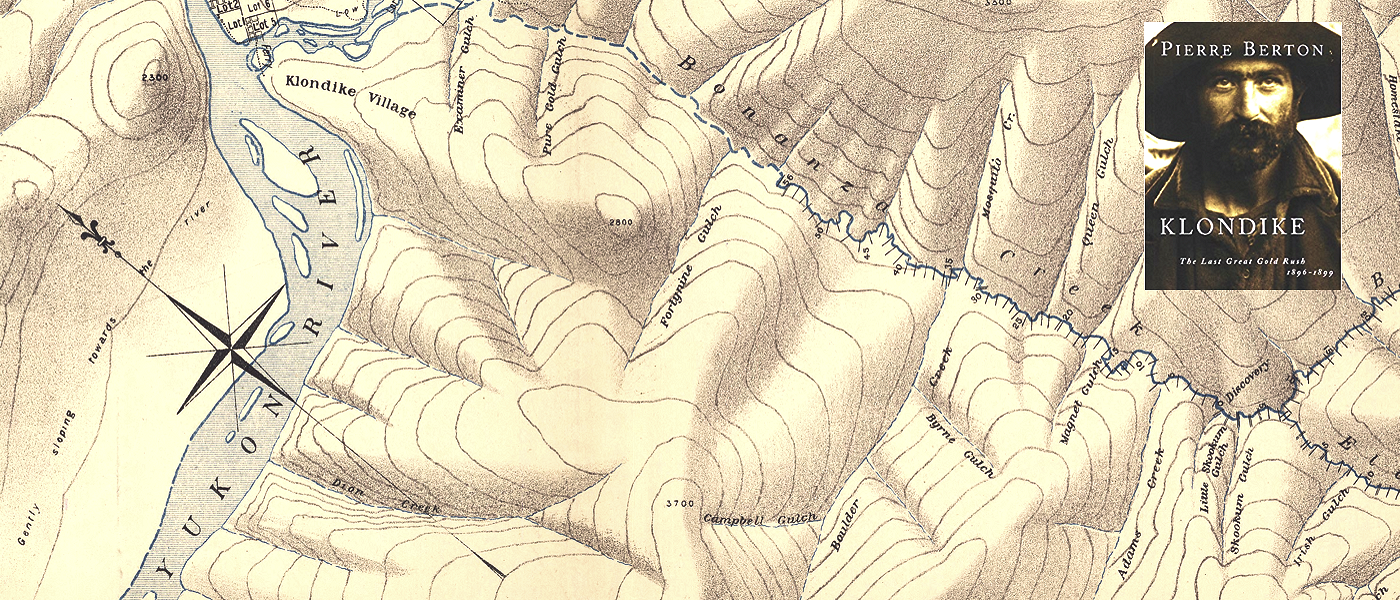

View the Yukon Map of 1898 on 10 sheets. You may also be interested in the Pierre Berton (Klondike) archives held at McMaster.

Permitted Use of the Maps: McMaster University Library is providing digital access to these topographic maps and the ability to download high resoultion copies (600 dpi, 1GB, .TIF) for non-commercial purposes only. For allowable use of the images found on this website, see the Creative Commons License.

Historical Context:

Shortly after British Columbia joined Canada in 1871, Ottawa petitioned the United States for a survey of the Alaskan Panhandle area to determine the exact location of the border, but Washington rejected the idea on the grounds that it would be too costly an investment for such a peripheral tract of land. In 1893 and 1894, using photo-topographic survey methods, W.F. King surveyed 5,000 square miles along the Alaska-B.C. boundary under orders from the Canadian Border Commission. In 1887 William Ogilvie was authorized by Ottawa to head an expedition to locate as definitely as possible the 141st meridian on the Yukon River. This action heralded the first direct attempt to fix with precision the Canada-United State boundary line in that part of North America.

The discovery of gold in the Yukon in 1896 led to a stampede to the Klondike region between 1897 and 1899. This led to the establishment of Dawson City in 1896, and subsequently, the Yukon Territory in 1898. Dawson, incidentally, was given its name by Ogilvie who was in charge of its layout in 1897. The name was chosen in honour of Dr. G.M. Dawson who is given partial credit on several sheets of the Yukon map. James Joseph McArthur, the surveyor in charge of the photo-topographic survey of the Rocky Mountains, is also given credit.

The gold rush brought to a head the ongoing border dispute in the contested Alaskan Panhandle area, which is a complex coastal area consisting of large fjords and channel islands. Canada wanted a direct route from the Klondike gold fields to the Pacific fjords, whereas the US wanted to maintain control of the intervening territory. A joint commission attempted to resolve the dispute in 1898–99 and failed. The problem was then referred to an international tribunal in 1903, whose members included three American politicians (Elihu Root, Henry Cabot Lodge and George Turner), two Canadians (Sir Allen Bristol Aylesworth and Sir Louis-Amable Jetté) and Lord Alverstone, Lord Chief Justice of England. The Canadian and American representatives favoured their respective governments’ territorial claims. Based on the 1825 Treaty of Saint Petersburg, it was clear that the border should lie 56 km east of the ocean coast, but it was not clear how the ocean coast should be defined. The Americans argued that the coast should be defined as the point where the mainland touches Pacific water, whereas the Canadians argued that the coast was at the western boundary of the channel islands. To the Canadians’ chagrin, Alverstone supported the American claim. Furious with what they saw as a betrayal by their colonial government, the Canadian representatives refused to sign the final decision. However, this act of protest did not prevent the decision from taking effect, since the question had been put to binding arbitration.

Though Canada lost the Alaska boundary dispute, the event marked a significant moment in which the country began to distinguish its political interests from both Britain and the United States.