'Gee' Radio Navigation and Precision Bombing

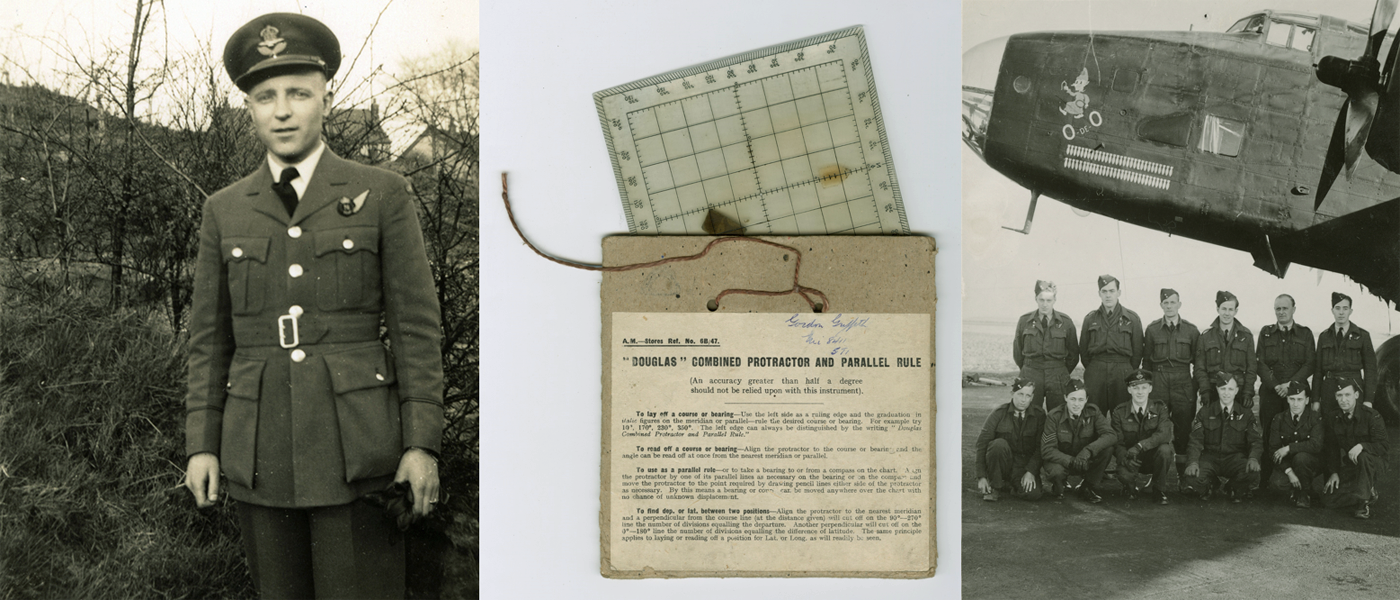

After the evacuation of British forces from Dunkirk and the fall of France, Britain had no ground forces on the continent and could only attack Germany through coastal Commando raids or through aerial bombardment. In 1940, daylight bombing raids had been attempted, but the losses were so appalling that bombing had to be shifted to the night in order to minimize casualties. However, the success of navigating a bomber hundreds of miles in the dark, through enemy anti-aircraft fire, using compass bearings, dead-reckoning and occasional visual checks between maps onboard and what could be seen through the window at 20,000 feet in often marginal weather conditions, was a next-to-impossible task.

Data compiled and analysed after the war confirmed that only approximately three out of every one hundred bombs fell within five miles of their intended targets. To increase the chances of success, bombing raids were switched to coastal targets as the border between land and water was more visible at night making features along it more easily identifiable. It was hoped that the bomber crews could follow these features, like breadcrumbs, to their ultimate targets. But it wasn't until 1942, and the introduction of electronic navigation aids like the 'Gee' system, that the words "precision" and "bombing" could truthfully be used together.

'Gee' allowed navigators to fix their positions on lattice charts by plotting the interception of hyperbolic radio signals from at least 2 or 3 transmitters based in the south of England. The first, large-scale, bombing raid using 'Gee' took place on May 30, 1942 with the city of Koln/Cologne as the target. Over 1,000 bombers successfully navigated their way to their target in darkness. Because it was a passive system that only required the bombing crews to receive signals, rather than transmit them, it did not give away the bomber positions to the enemy. 'Gee' had a drawback, however. It only had a range of about four hundred miles. After D-Day, sites had to be found on the continent for mobile 'Gee' transmitters which could be pushed forward as the allies advanced. This meant, of course, that the lattice charts based on these mobile 'Gee' stations had to be continuously updated. After the war, 'Gee' evolved into 'DECCA,' just as the American wartime equivalent, 'SHORAN,' transformed into 'LORAN.' Both systems would eventually be superseded by our current 'GPS' (Global Positiong System).

References and Recommended Reading:

Clough, A. B. (1952). The Second World War 1939-1945, Army Maps and Survey. London: War Office.

Hansen, Randall (2008). Fire and Fury: The Allied Bombing of Germany 1942-1945. Doubleday Canada.

Rankin, W. (2016). After the Map: Cartography, Navigation, and the Transformation of Territory in the Twentieth Century. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Thames Television Ltd. (Producer) Childs, Ted (Director), Home, Charles Douglas (Writer). (1973). The World at War: "Whirlwind," Bombing Germany September 1939-April 1944.