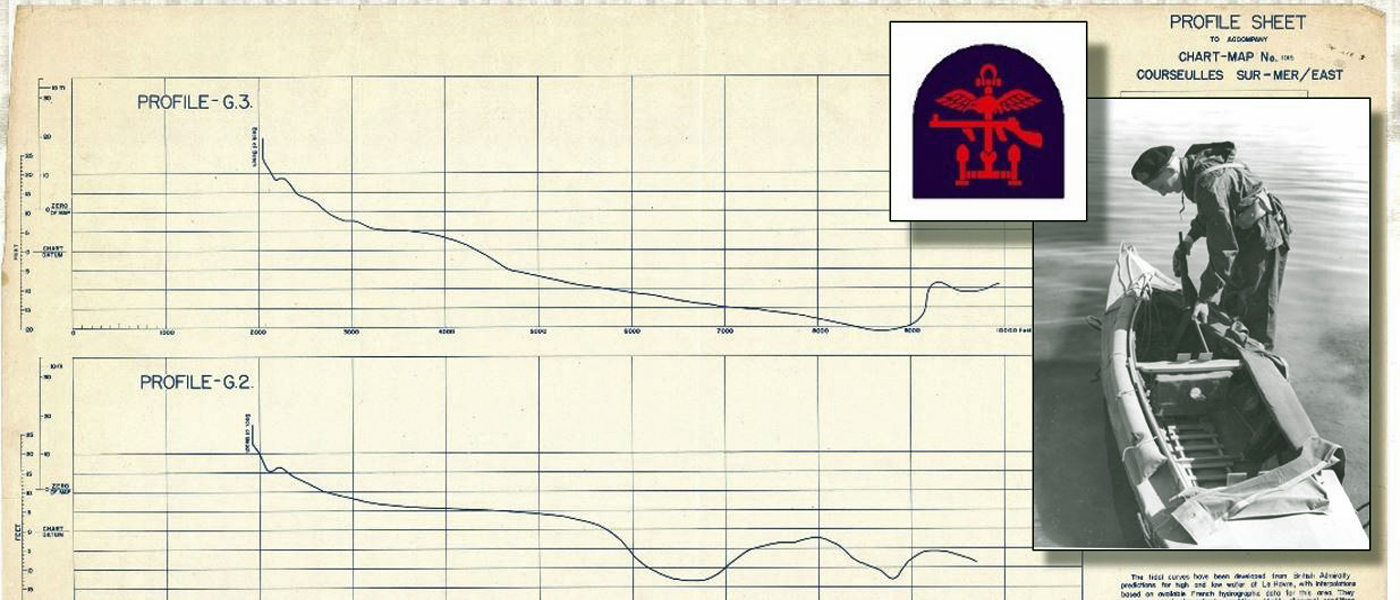

Beach Gradient Profiles

Note: The following Beach Gradient Profiles have been made available through an agreement between McMaster University and Wilfrid Laurier University. Paper originals are held at the Laurier Centre for Military, Strategic, and Disarmament Studies (LCMSDS).