Lucy Catherine Russell’s tragic death has been the primary subject of scholarly writing and discussion, if she is written about at all.

The curator behind a new digital exhibition from McMaster University Library is looking to shift the narrative.

Gillian Dunks, archives arrangement and description librarian at the William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections, has assembled an online time capsule of Lucy’s life with materials from her fonds at McMaster.

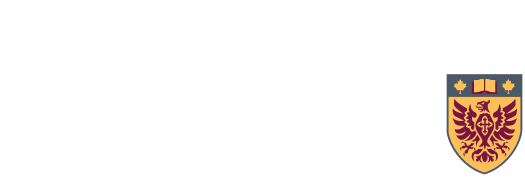

The resulting exhibit depicts Lucy—granddaughter of philosopher Bertrand Russell—as a bright, curious, and questioning woman.

“And Death Shall Have No Dominion”: Reframing the Life of Lucy Catherine Russell serves as a fitting close to McMaster University Library’s Year of Gender and Justice.

We spoke with Dunks about her experience working with the Lucy Catherine Russell fonds, surprises that came along the way, and how the exhibit is reinforcing the legacy of the Russell women.

Who was Lucy Catherine Russell?

Lucy Catherine Russell (1948-1975) was a granddaughter of Bertrand Russell, philosopher and peace activist. Her father, John Conrad Russell, was Bertrand Russell’s first son from his marriage to Dora Winnifred Black, also a social campaigner and peace activist. Lucy’s mother, Susan Lindsay, was the daughter of American poet Vachel Lindsay.

Lucy has been described by Ray Monk, one of Russell’s biographers, as Bertrand Russell’s “favorite” grandchild—someone who occupied an important place in Russell’s life during his final years. Lucy was a bright, curious person who was interested in mathematics, literature, and art.

Why did you choose to curate an online exhibition about her?

In February 2022, the Department of Archives and Research Collections acquired Lucy Russell’s archive from Ray Monk. Lucy’s papers had originally been entrusted to one of her childhood friends, Siân Cooper-Willis. Cooper-Willis passed these papers on to Ray Monk.

Lucy’s papers present the opportunity for a critical reappraisal of her life, now that there is more extant material available to scholars. When Lucy has been written about, she is often a tragic footnote at the end of Bertrand Russell’s story. Lucy had schizophrenia, as Russell’s son John did, and died by self-immolation at the age of 26. Her life has often been viewed exclusively through the lens of her death, but there is more to her story, including her own perspective on the Russell family.

The exhibit is called, “And Death Shall Have No Dominion”: Reframing the Life of Lucy Catherine Russell.

What is the meaning behind the exhibit’s title?

The title is a line in Dylan Thomas’s poem, “And death shall have no dominion.” Lucy was a great fan of this poem and copied it out many times in her notebooks. The first stanza reads:

“And death shall have no dominion.

Dead men naked they shall be one

With the man in the wind and the west moon;

When their bones are picked clean and the clean bones gone,

They shall have stars at elbow and foot;

Though they go mad they shall be sane,

Though they sink through the sea they shall rise again;

Though lovers be lost love shall not;

And death shall have no dominion.”

As the goal of this exhibit is to encourage critical reappraisals of Lucy’s life, beyond the fact of her death, this poem is apt.

What types of materials are included in this digital exhibit?

The exhibit includes Lucy’s correspondence, diary excerpts, family photographs, and artwork.

What do you hope people learn from this exhibit?

Many people are familiar with Bertrand Russell’s life story, but I hope this exhibit brings greater awareness to the lives of the young women in the Russell family—not just Lucy, but also her sisters, Sarah and Anne, whose photographs and letters are included in the exhibit, too.

What was your experience like curating this exhibit?

I was fortunate to catalogue the Lucy Russell fonds, so I was already very familiar with Lucy’s archive when the time came to curate this exhibit. I knew right away when I started cataloguing the archive that it was special, so as I worked, I flagged items that might be of interest to the public.

One of the most meaningful aspects of curation has been corresponding with Harriet Ward, Lucy’s aunt, who granted permission for the inclusion of a letter from Dora Russell (Lucy’s grandmother) in the final exhibit. I am very grateful for Ms. Ward’s openness in sharing her family’s story.

Which item is your favourite and why?

My favourite item is a scrapbook created by Lucy, likely sometime between 1958-1965, when she was a teenager. The scrapbook features casual family photographs with Lucy’s own captions. It provides an intimate and often funny set of insights into the life of the Russell family at home (see Box 20, File 1 of Lucy’s archive). I am also partial to Lucy’s cartoon doodles and drawings, which were frequently interfiled with her school notebooks. I have included one in the exhibit (see Box 7, File 2).

What surprising facts did you learn about Lucy during curation?

Lucy was quite skilled at languages! She appears to have been fluent in French, as her correspondence shows, and her school notebooks reveal she studied Latin, Greek, and Spanish as well. She also had facility in painting and drawing.

Is there anything else you’d like people to know about Lucy Russell or the exhibit?

I encourage anyone who is interested in learning more about Lucy to consult her archive in person, as there is a lot more content available. There are 25 boxes of records from Lucy, all stored at the Bertrand Russell Archives at 88 Forsyth Ave. N. There are also smaller archives from Lucy’s sisters, Sarah and Anne, at the Russell Archives.