The “Phoney war” is a period of restless waiting between September 1939 and May 1940, when the war has already started but the Western Allies were not actively involved in any military operations with the Nazi Germany. Anxiety is the emotion that dominates both archival documents of that epoch and the VHA interviews, with people waiting for the inevitable war to happen:

When I came back to Paris, we were just waiting for things to start happening; but nothing happened, people were just scared… After the invasion of Belgium and Holland, many refugees would come to France. Many refugees’ camps were established, where these people could stay.[*]

In the VHA interview, Regine Barshak remembers how at the age of fourteen, right after the declaration of war, she started noticing that some of her classmates had the names that did not sound very French, not Dubois or Dumont; but rather Zimmerman or Weimann. Many of these children belonged to the families that emigrated from the Nazi Germany trying to avoid anti-Semitic laws. Along with the conversations she heard from the adults, the atmosphere was "one of a great fear of the oncoming war."[*]

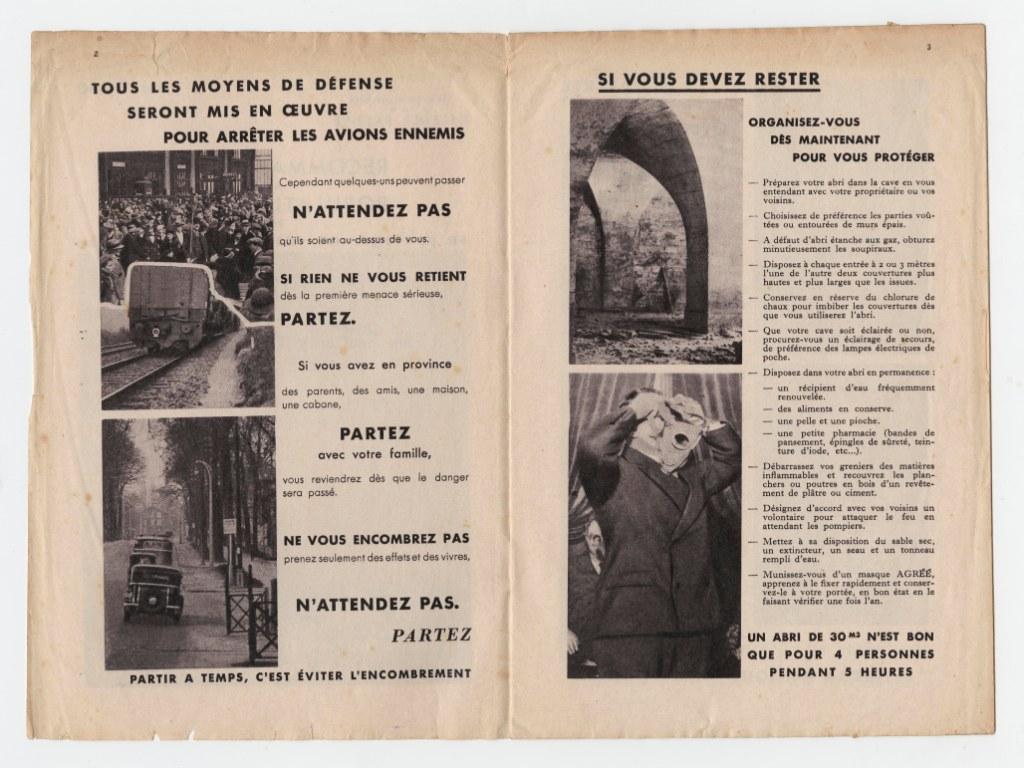

The documents also demonstrate that the population must have experienced high levels of anxiety, when being instructed how to behave during gas attacks and air raids. The illustrated pamphlet contains the detailed illustrations and numerous reminders to “read and keep this brochure. It can save your life one day." Another event featured in the documents is the Benefit Sale of February 1940, supporting the mobilised so10ldiers; at the same time, the other side of this card contains the information about a POW soldier incarcerated in the Stalag camp.

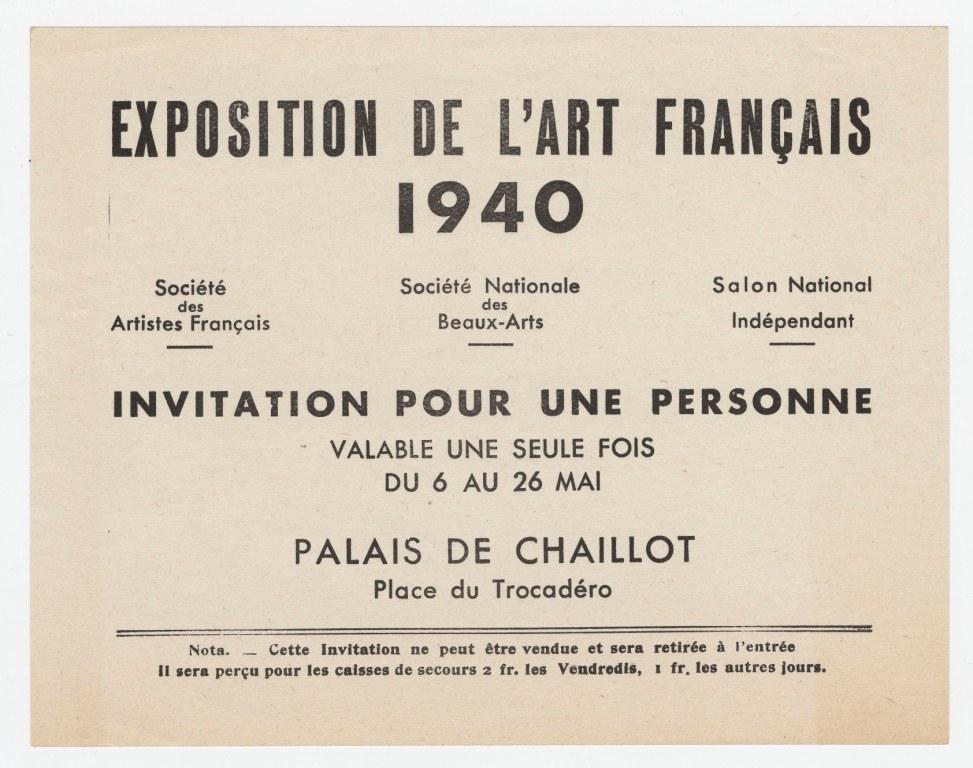

After the initial shock, life would continue: people would go to school, see their friends, and work: “Paris changed already in 1939 when the curfew was imposed. Street lighting was turned into blue, and the shop lighting was cut back. It was very dark and depressing when I came home. I was frightened when I got back to Paris but the young people adapted very quickly to the new conditions.[*] One of the last documents of this epoch held at the Brisebois collection is a card announcing the exhibition of the French art. The event was meant to happen on May 6-26, 1940; with the Nazi invasion of May 10, 1940, one cannot say if the exhibition ever took place. However, this document gives us an insight into one of the last peaceful activities before the great disaster came.

Tavy Notton on Hunger in Greece

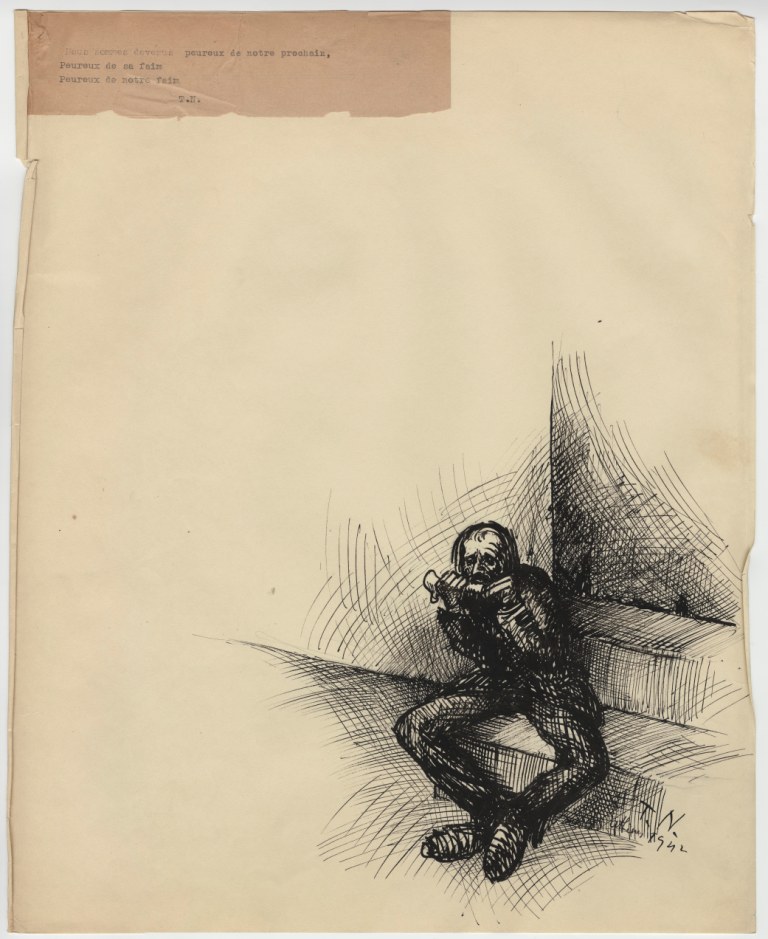

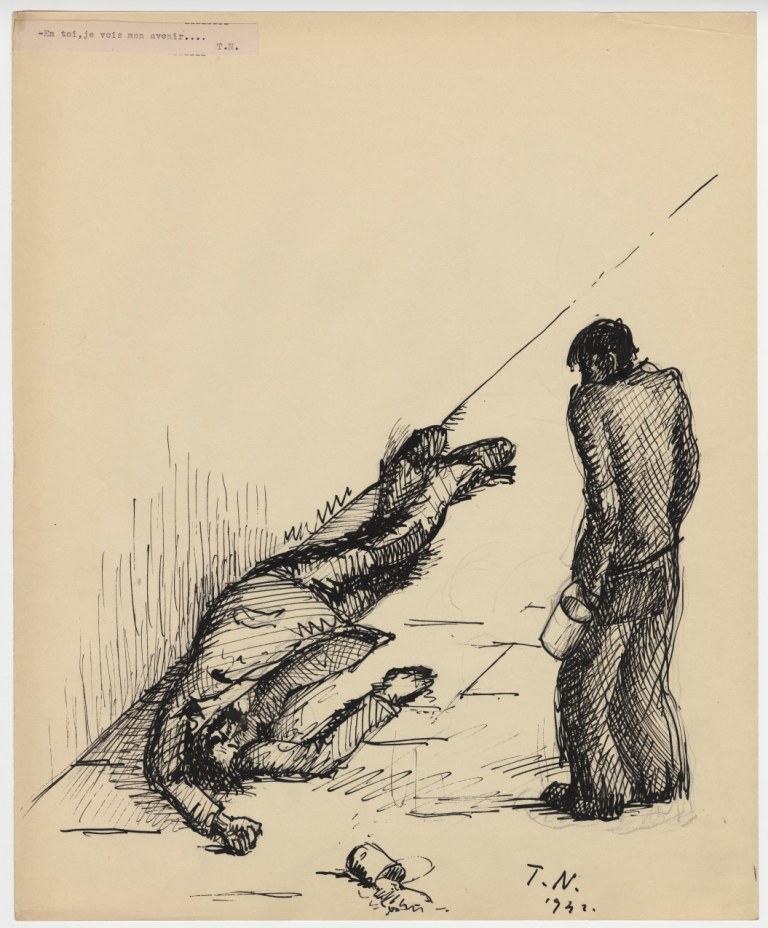

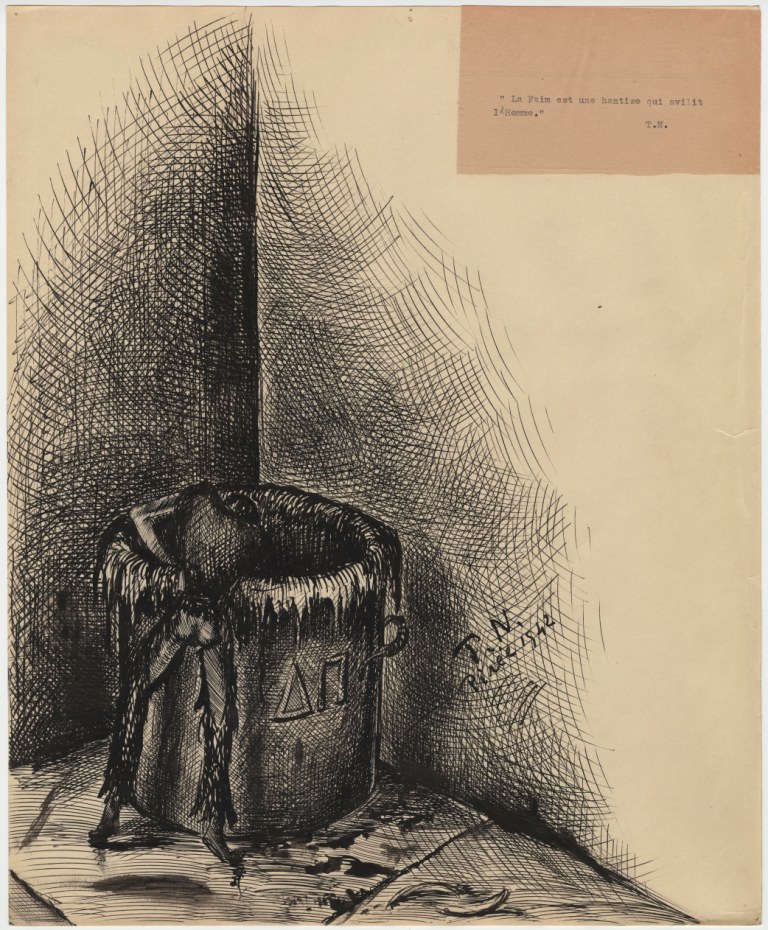

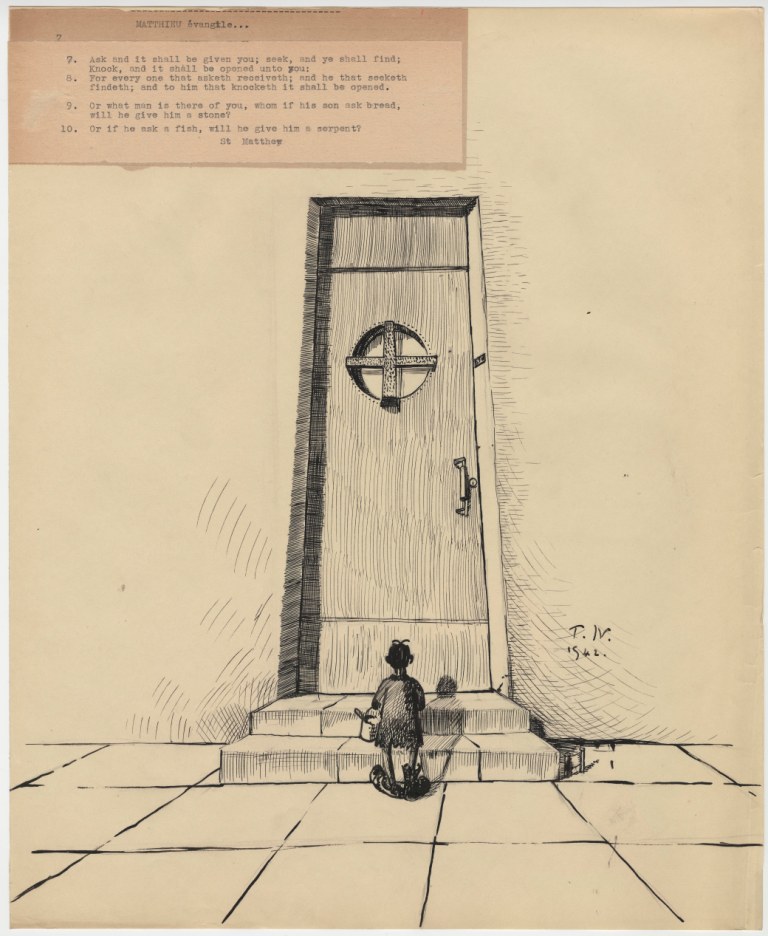

One of the darkest illustrations of horrors of war and Holocaust belongs to Tavy Notton, Greek-French artist and illustrator. The archive holds a set of his drawings, dated between 1941 and 1944, depicting the Great Famine in Greece, yet another gruesome consequence of the Nazi occupation. The pictures are also supplemented by the French text describing the occupation of Greece. While the information about this powerful artist is extremely scarce (we know that his illustrations appeared in different books, such as Maeterlinck, Gide, and others), the document speaks for itself and shows us the tragedy of Greek people:

The entire city is starving, the entire city is scared of dying of hunger, the entire city cries, moans: “Mother, I am hungry!” The entire population is transformed into the horde, with the staring eyes, their thoughts fixed on groceries... The entire population is debased by the horror of hunger.

In the beginning of war, after the successful defeat of the first attack of Italy, Greece was occupied by Germany. “Within the first months of occupation Germans seized or bought at low prices – paying with the ‘occupational marks’ they circulated – all available stocks of olive oil, olives, raisins, figs, tobacco, cotton, leather and the majority of pack animals. The appropriation of all means of transport (including bicycles on Hios) and fuel by the occupying authorities effectively prevented any movement of supplies or population after the invasion. Fishing was strictly prohibited, at least in the early stages of the occupation <…>” (13)

As a result, the people started dying of starvation, malnutrition, and hunger-related diseases. In the VHA interview, Sarah Cohen remembers: “There was no food at all. We started having, instead of regular bread, a piece of corn-made bread that they gave us once a day… People started to die. We just could not find any food. People started dying on the streets; many of us had typhus, because of malnutrition.[*] To save themselves, the people would sell everything they had in exchange for some food at the black market. Another VHA interviewee tells how his family had to sell the priceless pieces of furniture for 300 pounds of flour.[*] With the constant expropriation of all food supplies, the prohibition of any transportation between the islands and cities, and the Allies’ blockade of Greece, the famine soon became widespread and massive. According to the historian of this period, <…> there is no accurate figure of famine deaths for the whole of Greece other than some… estimates. For example, the figures 100,000, 200,000, 250000 and 4500000 have been suggested. [*]

This tragic history is captured and reflected by the writings and drawings of Tavy Notton. Seeing himself both a witness and a participant of his country’s suffering, he wonders through the towns and villages, and transfers his experience both into words and pictures. In the very conclusion of his monologue, he explains that his stories are not the imprints of facts that he witnessed but also a way to liberate himself at least partially of his traumatic experience:

The famine, I am starving, you are starving, we are suffering from the famine, abominable living skeletons, vacillating, undulating like withering plants, abominable tearful ghosts, whirling in my memory, I want to draw you, now that I can remember you. Yes! I remember. I remember. The pencil squeaks furiously on paper, delivering my visions of pools of black blood, of my nightmares, of my fear. Finally, my thoughts are visible. These nightmares have been taken away from me...

Notton’s pictures are full of dark and hopeless images: here is a man gnawing a bone like an animal; here is a boy picking up the crumbs from the street; and here are two starving children. The horrors of the famine are depicted without any veil, as the witnesses saw it in their everyday life:

They [the Germans] came by the railways, and took almost everything available. There was absolutely no food, and people were dying. I will never forget – I went to school, and I saw little children aged 6,4,5, looking into garbage looking for food.[*]

Tavy Notton’s text is mostly centered on emotions and feelings of a witness and a victim of the great famine in Greece. He writes repeatedly about the “being afraid of famine”, of a great horror of starvation. He also picks some small occurrences and turns them into stories, similar to his drawings. These scenes become the most authentic testimonies of people’s bravery and suffering during the Occupation:

[Someone knocks at the door]

This is a starving person again. But oh my God, I am starving as well, and we do not have anything at all, a plate of boiled corn with a bit of onion. That’s it...

I open anyway. This is a young man, with the hollow face, with the rolled-back eyes, like the saints of El Greco, nostrils plucked, the corners of his lips bleached with the drips of saliva. He does not say anything, I look at him, I look at him. Our looks penetrate, probe each other. I am thinking about what we could give him. But what? Bread? Beautiful irony... Fresh, powdery bread. He is starving, his hunger is terrible...

- Andree, this man is starving. Do we have something for him?

- Good God! Yes! I am starving, a hunger that does not diminish, the hunger that I knew I would survive remains forever in my memory as a material thought. I was in France. I have seen all kinds of things. I returned to my country to fight the enemy, and yet now I am a beggar.

- No! You are not a beggar. And to prove this, you are going to dine with us. It won’t be much, but glory to the God, our teeth are chewing something, and tomorrow, we will see if the one I have just glorified will lead me to his heart.

Liberation cartoons

In the war narratives, the stories of liberation and the war's end is highly emotional moment. The former prisoners describe their final struggles with illnesses and starvation, while others focus on their attempts to re-adjust to the normal life. Thus, Bejla Blustajn in the VHA interview describes how she, along with her friends, was walking along the road with the American soldiers, all in tears: “We kept crying for many days, we thought that we are getting sick because we could not stop.[*]

But sometimes the events are described in a humorous tone, even when tackling the themes of hunger and mortal danger. In another VHA story, the survivor lightly talks about the end of the war, and how it seemed that the salvation was impossible:

I finally got out of the coal pile, and we back to the companion. There was shooting. There was another guy, we thought that this is the end, we had a cook stick, a galore, and stuffed ourselves with food... And the next thing, somebody came running in, crying “the Americans are here!” And we went outside, and I saw the young kid in the uniform. I went up to him and said “You – American?” That was it, we were liberated.[*]

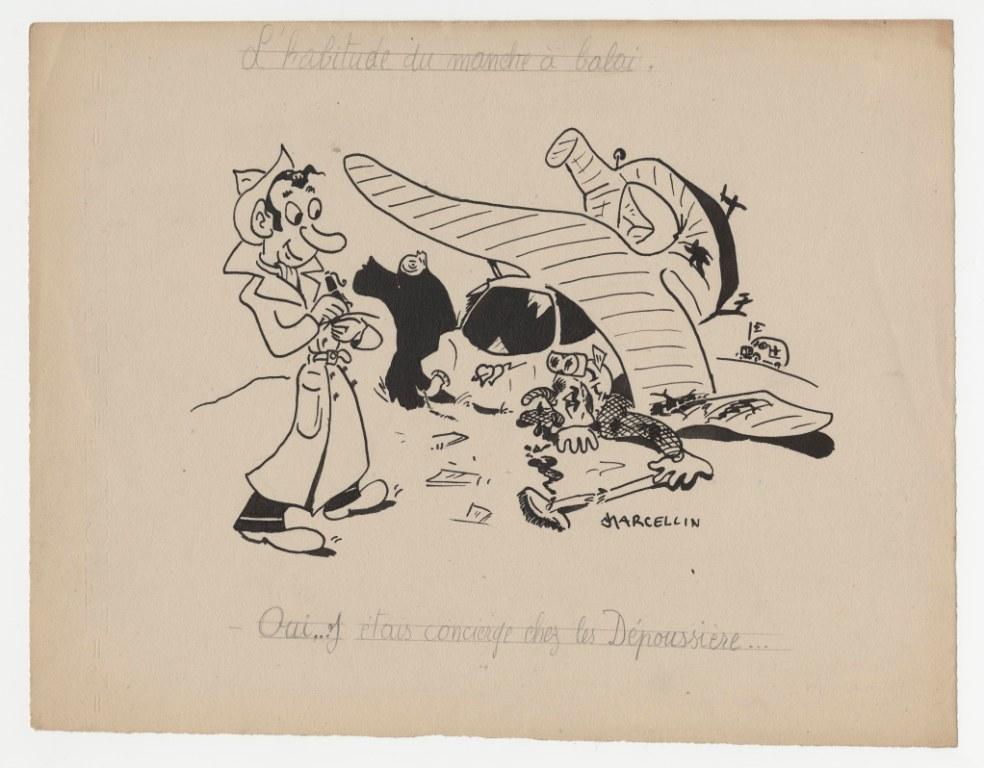

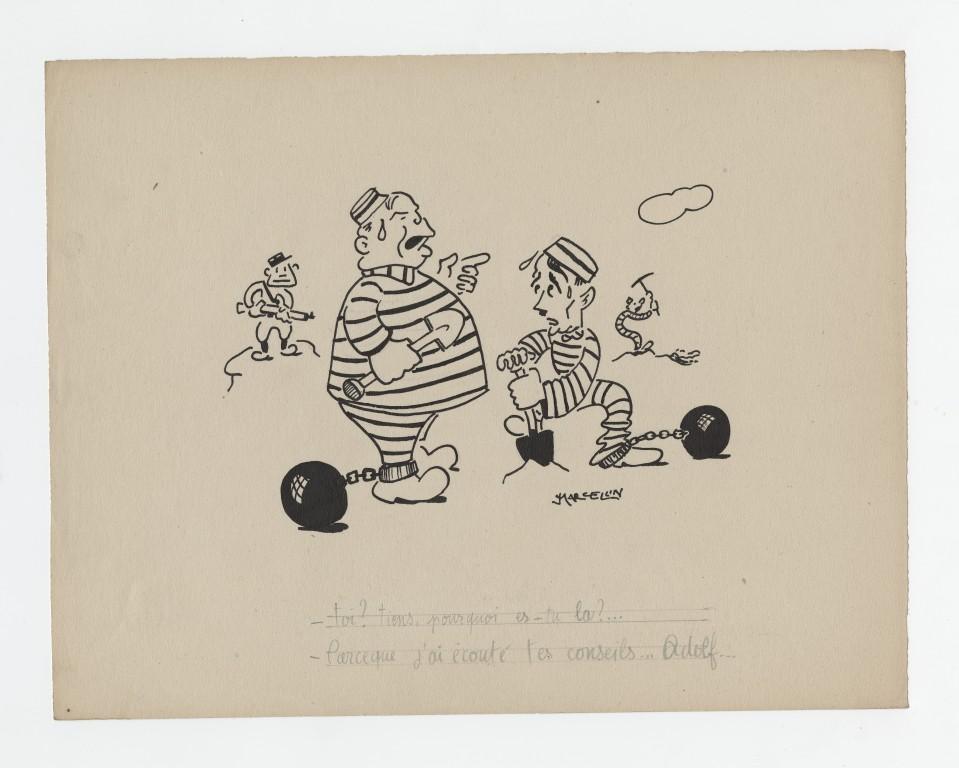

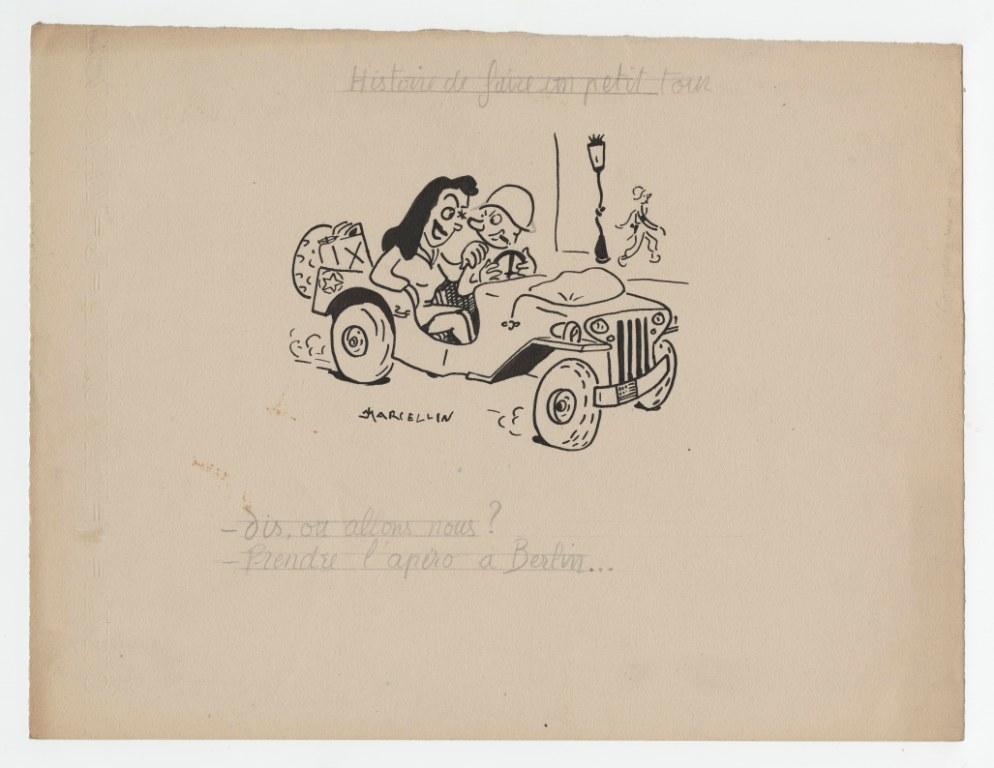

Among the documents that belong to the liberation time, the Brisebois collection holds 12 caricatures drawn by the young artist Jean Marcellin. His cartoons are full of sarcasm and laughter, celebrating the liberation of his native region, Vaison-la-Romaine. Jean Marcellin (born 1928), is a French cartoonist that started his artistic career as an illustrator of the book “Histoire du Maquis Vasio” published in 1945. Dedicated to the French resistance group of Vaison-la-Romaine region, this book commemorates the heroes of the Resistance, as well as focuses on the major moment of the history of this group. The stories are supplied by the drawings of Jean Marcellin, created exclusively for this book. For Marcellin, this book became his artistic debut; after that, he “settled in Paris in the following year and produced animated films for the advertising field.” Throughout his life, he drew pictures for various French magazines and journals, as well as illustrated many children’s and adult books. There was recently his exhibition, hosted by the Ferme des Arts in March 2014.

Along with ridiculing the conquered Nazis, Marcellin's drawings also celebrate the freedom, similarly to how the actual witnesses talk about that [*] This light tone allows us to experience not only grief and horror but also the feeling of the utmost joy and redemption.

NOTES

[1] Irene Abrams, Interview 23769, Visual History Archive, USC Shoah Foundation Institute. Web 21 Aug 2014.

[2] Regine Barshak, Interview 1844, Visual History Archive, USC Shoah Foundation Institute. Web 21 Aug 2014.

[3] Jacques Adler, Interview 36093, Visual History Archive, USC Shoah Foundation Institute. Web 21 Aug 2014.

[4] Sarah Cohen, Interview 1699, Visual History Archive, USC Shoah Foundation Institute. Web 21 Aug 2014.

[5] Ray Naar, Interview 33353, Visual History Archive, USC Shoah Foundation Institute. Web 21 Aug 2014.

[6] Hionidou, Violetta, Famine and Death in Occupied Greece, 1941-1944. Cambridge, UK ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006, p. 25

[7] Ya`aḳov Ḥa´ndali, Interview 1654, Visual History Archive, USC Shoah Foundation Institute. Web 21 Aug 2014.

[8] Bejla Blustajn, Interview 24573, Visual History Archive, USC Shoah Foundation Institute. Web 21 Aug 2014.

[9] Henry Alexander, Interview 3857, Visual History Archive, USC Shoah Foundation Institute. Web 21 Aug 2014.

[10] Georgette Banks, Interview 8139, Visual History Archive, USC Shoah Foundation Institute. Web 21 Aug 2014.