The Diamant Collection holds a testimony of a young Polish-Jewish woman who survived the destruction of Warsaw ghetto, reprinted by the National Movement against Racism. This French underground unit was mostly engaged in the humanitarian acts of resistance, such as hiding people, rescuing children, distributing false papers, gathering food for Jews, etc. Among other things they published an underground newspaper, J’accuse, that notified the population of the mass killings of Jews in ghettos and camps. Similarly, the Testimony of a young female survivor of the Warsaw Ghetto is not just a personal story but a means of informing the people in France about the horrors of persecution happening in Eastern Europe. Written by a young girl, this letter describes how her family tried to escape eastward from Lodz, to the Soviet-controlled territory of Poland. Having no means of transportation, they walked on foot for two weeks, only to find that getting to the Soviet territory was impossible, because “the Germans established a fence on the border. Many of my friends were captured and sent to a concentration camp.” After spending six weeks in Lublin, the family returned to Lodz:

The first days of the enemy occupation, especially in those parts which belonged to Germany in 1914, were horrible. The Germans satisfied their hatred by killing thousands of their political adversaries and by persecuting, specifically, intellectuals. They arrested hundreds of priests. All the shopkeepers and peasants were deported, their properties allocated to the Germans. <…> The city of Lodz was completely Germanized. Inscriptions, compulsory Germany served to demonstrate the Germanism of the city. Poles, especially intellectuals, were arrested en masse. They expropriated Jews, and their shops and apartments became the property of the Germans who were forced to leave the Baltics. Early on, the Jews were ordered to wear a star on their chests and another on their backs. They didn’t have the right to be other than at the back of streetcars. The police hour, or the curfew, starts at 6 pm; if they catch you, they will take your ration cards, or worse.[*]

Later, her family, along with the thousands of other people, was chased into the Warsaw ghetto, where she experienced hunger, malnourishment, typhus and violence of the guards. After witnessing her mother being taken away (probably to the death camp) the girl “spent that night on the balcony of the fourth floor with the idea of committing suicide; the courage to throw myself on the road escaped me. Who would take care of my sick father and young sister?” Her family perished anyway, her father and sister were killed when the Warsaw uprising began. The girl was able to escape from the ghetto, with the help of her Christian classmates, and lived in Warsaw at her friend’s place for another six weeks watching the “blaze of the ghetto lighting up Warsaw.” Fearing to inflict the mortal danger on her Polish friend, she managed to leave the city and get to Switzerland. She ends her account with the phrase, “I am only 22 years old but it seems to me that I have suffered for a century.”

Reprinted by the Resistance as a survivor’s testimony, this text is designed as a leaflet drawing the attention of people in France to the atrocities in Poland. Along with the personal story of a single family, this letter also gathers the essence and chronology of the Warsaw uprising. The survivor probably witnessed some things, while some of them were added later. One of the ghetto scenes describing the deportation of the orphanage of Janusz Korczak from Warsaw to Treblinka death camp could be her own recollection or could have been heard as a story:

One day I saw a moving procession: a long line of children marching two-by-two, holding each others' hands, all formally dressed. At the head was Korczak, a very old man, with long white hair. Korczak was a known writer, an author of magnificent children's books, a generous man who devoted his life to the well-being of children. He had created a model orphanage. He did not want to abandon the little ones in their last journey and marched with them towards their death.

Being full of graphic descriptions of horrors and cruelties, this letter does not have any additional notes from the Resistance that distributed the document. As the witness points out, “I have told you but a small portion of the horrors that I have seen and lived.” This text constitutes a powerful example of how the Resistance used different narratives, including personal testimonies, to spread the truth about the mass murders among the French people.

In France, many Polish nationals, both Jewish and Gentiles, lived in the Nord-pas de Calais region. Some of them had grown up there and spoke French, while others immigrated or fled from Poland when the threat of war became evident. Thus, the Polish-Jewish survivor Bertold Lande says that he moved to France before the war started, to study law in Strasbourg. This probably saved his life, as the rest of his family stayed in Lwow: “I encouraged my parents to sell everything and to get out of Poland but they refused. They could not expect what could happen.”[*] He could never find out what happened to his parents; he says that most likely they were murdered by the local collaborators. According to a document written by the Polish Committee for the National Liberation Movement, there were 500,000 Polish immigrants living in France by 1944:

On French soil there are 500,000 Poles of whom 40% serve in the departments in Pas de Calais and the North. The immigration's contribution to France's national economy is notable in the coal industry, and is also very considerable in agriculture. Like miners, Poles, while performing the most painful, hard and dangerous work, in no small way ensure the functioning of all French economic activity, given that a very high percentage of French coal extraction is due to Polish labor.

The Polish played an important role in the famous strike of 100,000 miners during 1941 in German occupied France. The Polish were among the first to take arms against the occupancy, we remember all those who gloriously fell in the defense of France and Poland.[*]

While addressing the President of the National Council for Resistance (CNR), namely, Charles de Gaulle, the letter asks to “officially recognize the Polish National Committee for Liberation as official representatives of the Polish community in France.” At this point, when the British and American forces often helped the resistance groups by parachuting them ammunition and supplies, official recognition for the underground was vital. As Maurice Asa states, “There were lots of conflicts between the armed resistance. There was the resistance supported by the British intelligence service, and the one supported by the Free French, De Gaulle. And these two could not stand each other! <…> We were all against Germans but there were conflicts, who would get more arms, who would do this or that.”

Another letter, coming from the same organization, also speaks of the necessity of recognizing them as the leading group among the French Poles:

A National Polish Committee for liberation has been elected, who will represent the Polish people within France, and who sees their principle task as mobilizing all Polish energies in the struggle against the common enemy. The National Polish Committee for Liberation with it brings the membership of 500,000 enthusiastic Poles, who see the provisional government in the Algiers and the CNR as their sole French authority and who burn with anticipation to fight under a French-Polish flag.[*]

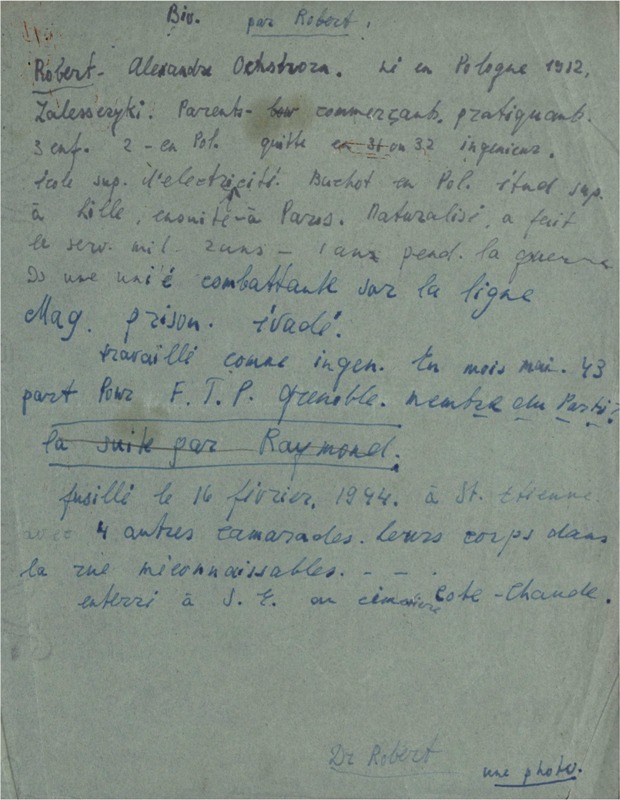

The document also commemorates a number of the resistance fighters that struggled and fell side by side with the French partisans, including Stanislas Kubacki,[*] who was “shot in Pairs in March of 1944, along with 21 other patriots, both immigrants and French.” Kubacki was one of the members of the Manouchian group, the French partisan, who was active in the Francs Tireurs et Partisans - Main - d'oeuvre immigrée units. They were mainly engaged in the acts of sabotage, attacks on the German soldiers, and derailing Nazi trains. The group consisted of 23 people, French and other nationalities, including 8 Poles. Arrested in late 1943, all of them were tortured and executed on February 21, 1944.[*]

The Polish resistance in France was also supported by the Polish government in exile. When Bertold Lande realized that he needed to escape from occupied France to Spain he started looking for money, since he needed a guide that would take him over the mountains to the border:

At that time I applied for the Polish grant, I went there, and the man said – yes, you will get a loan. But I had to sign the paper that as soon as I get across the border [to Spain] I had to report to the Polish army. I got the paper and the money and decided to try to cross the Spanish border.

The Polish government in exile had some money that they were probably getting from the British or Americans; they were mostly helping the Christian Poles who escaped from Germany or German army. I even met a fellow at this Polish office from my hometown. They even gave me a name of the guide.[*]

After crossing the Spanish border and serving his time in the internment camps and prisons Bertold Lande was released, sailed to England, and joined the Polish army in exile. In the VHA interview, he notes that the Polish army consisted of not only the refugees but also the former soldiers from the Wehrmacht that were sent to Africa, captured there by the British forces as the prisoners of war. After being brought to England, the soldiers would volunteer to go to the Polish or British army and fight against the Nazis. The Resistance also thought about how to persuade these soldiers to abandon the German army. In one of the reports produced by the Jeunesse Communiste Juive (Young Jewish Communists) different ways of such agitation are discussed, including the verbal and written slogans. Due to the strong “Jewish accent” that many of the Polish-speaking resisters had the group adopted the following strategy:

A two inscriptions in Polish were made with the following slogans: "Hitler lost the war.

Polish soldiers, desert and rebel!

These inscriptions have produced a large effect on the morale of soldiers, and teams of German soldiers come every morning with pots of paint to cover our inscriptions that will reappear through the new layers.

In addition, our shock groups have framed a group from the Party for creating the inscriptions.

They are going to receive the Polish material for the soldiers, and at the beginning of June, the distribution of this material will be made.[*]

To be a refugee in a foreign country is hard enough; to hide in the foreign country in a time of war and persecution is a dire trial for any person. The illegal immigrants or Jewish refugees in hiding had to live day by day, getting food ration cards, evading the roundups, and trying somehow to function on a daily basis. The documents from the Diamant Collection, along with the VHA interviews, vividly demonstrate the degree of this tension that such a refugee in a foreign country experienced.

NOTES

[1] 0137 Mouvement national contre le racisme. Témoignage d'une jeune femme survivante du ghetto de Varsovie.

[2] Lande, Bertold, Interview 16963, Visual History Archive. USC Shoah Foundation Institute. 2013. Web. 8 July 2013.

[3] 0139 Le Comité Polonais de la Libération Nation ale en France au Président du Conseil National de la Résistance. Juin 1944.

[4] 0140 Lettre de la Conférence nationale d'unité de l'immigration polonaise en France au Conseil National de la Résistance. Avril 1944

[5] 0099 Jeunes communistes juifs - rapport mensuel. Mai 1944