A substantial part of the Brisebois collection consists of letters sent by women from various places of confinement, mostly from Ravensbrück, a concentration camp that was organized specially for women. There were more than 50 subcamps associated with Ravensbrück, where prisoners were forced to work for German factories (e.g. Siemens) to produce armaments for the war. Overall, 130,000 people passed through this camp, of which 20,000 were men. More than half of these women were young, less than 30 years old. Only 30,000 survived the war, and most of the children born in the camp died before the liberation.[*] The fact that Ravensbrück has been populated by women only did not bring any alleviation in the everyday life of the prisoners; many inmates of this camp died because of malnutrition, were shot, hanged or sent to the gas chamber. Ravensbrück is also known for the medical experiments conducted on women, an act that left almost all of them handicapped. However, as noted by Jack Morrison in the book Ravensbrück: Everyday Life in a Women’s Concentration Camp 1939-1945, “Ravensbrück inmates displayed survival skills based upon abilities and outlooks unique to women prisoners... Most of them knew how to extend and apportion a restricted food supply, how to darn socks and downsize a jacket, and how to fashion a carry-bag out of rags... They knew how to deal with cuts and bruises, and how to make a poultice for a sick child. Skills such as these had direct applications in a concentration camp, and their prevalence in a camp for women made it a more tolerable and survivable place than it might have been otherwise.”[*]

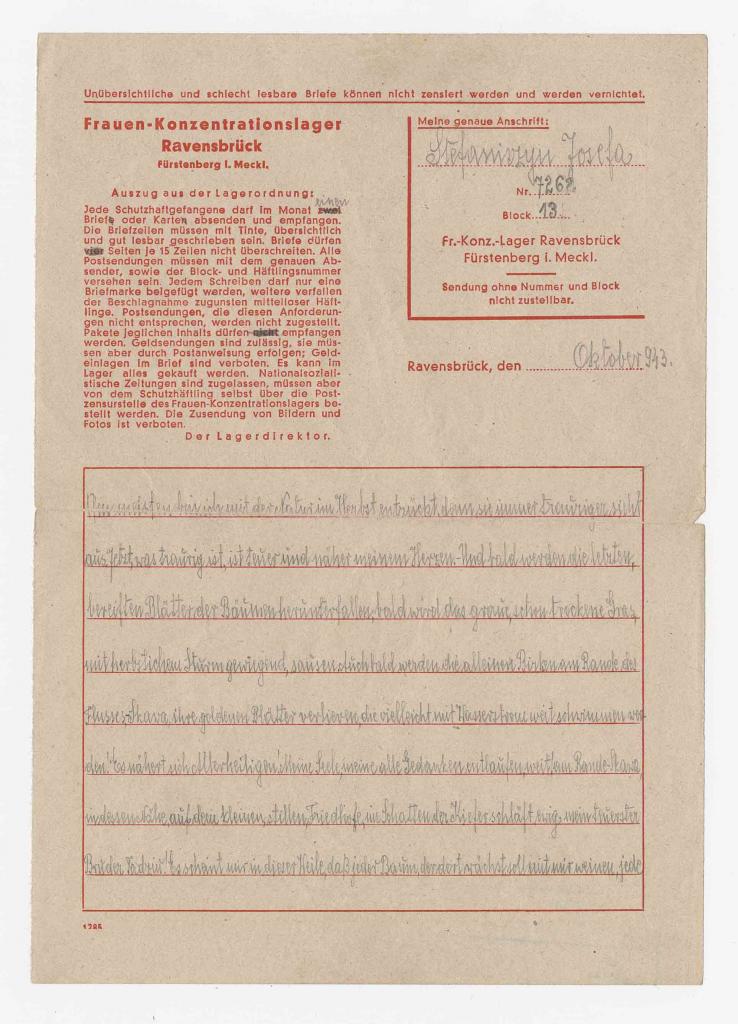

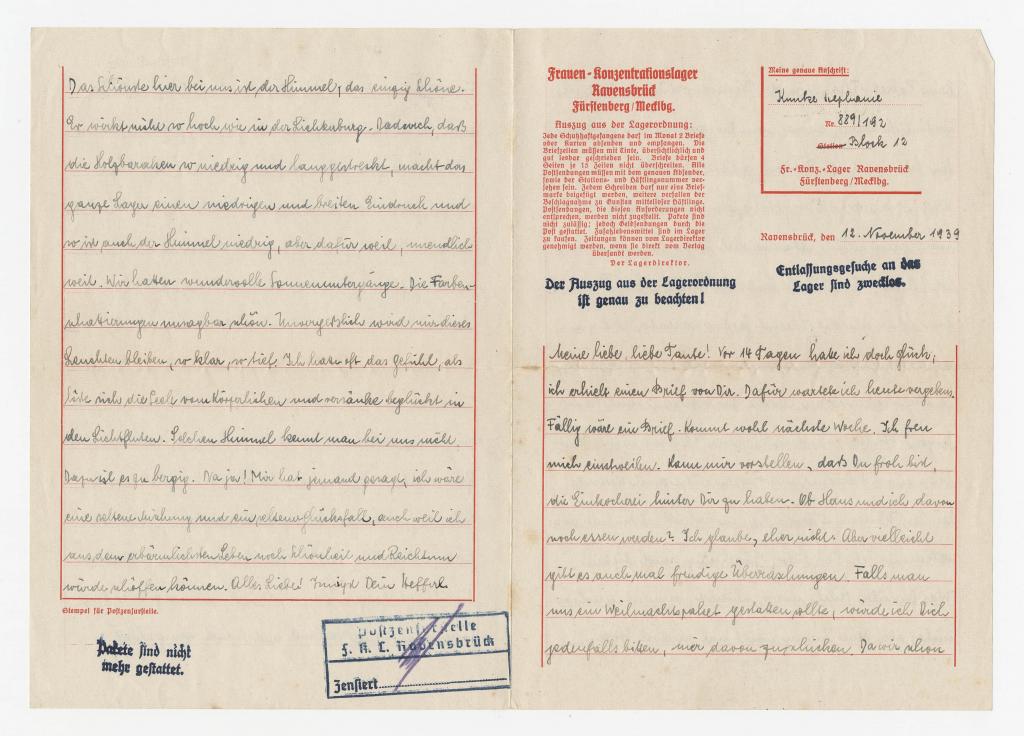

For us today, the letters of Ravensbrück inmates represent visual illustrations of such exemplary stoutness. Even within the strict limits of the format prescribed by the SS censorship they managed to convey their camp experience to relatives so that one could feel their true emotion. The correspondence of Stephanie Kunke provides us with the testimony that preserves the history of this courageous woman. Born in Vienna on December 26, 1908, she became an active socialist, along with her husband Hans Kunke. One of the pre-war acquaintances of this couple remembers how they met after the brief civil war that broke out in Austria in 1934: “As a result the Socialist party was outlawed and material that could have incriminated its members had to be destroyed,” and the Kunke couple was actively involved in helping to hide any evidence.[*] In 1938, Hans and Steffi were arrested and put into prison; afterwards, both went to different concentration camps, from which neither of them returned. Hans ended up in Buchenwald at the sock-darning labour detachment. Being severely abused, on October 31, 1940 “in act of desperation [he] ran through guard chain and was shot to death.”[*]

Steffi outlived her husband by a few years: after a brief stay at Lichtenburg concentration camp, she was deported to Ravensbrück, where, because of her political activity, she had to spend two years at Strafblock (according to testimonies, this “Punishment block” rated next to the gas chamber). The inmates of the Strafblock were forced to do extremely hard construction work, they had to carry heavy rocks, and move huge blocks, often without food or rest. In the beginning of 1941, she was released from Strafblock and placed in Block 1 with the political prisoners, under the guidance of Rosa Jochmann.[*] Steffi’s friend from Ravensbrück remembers that “this was the best time for her in the camp,” as she was able to write and to be with her peers. In early 1942 Stephanie, together with other German comrades, was sent to Auschwitz, where she died on February 14, 1943.

People who knew Steffi before the war or even in camp characterize her as a talented writer and a joyful person. Stella Klein-Low met Stephanie and Hans in Vienna in the 1930s “when they helped her to dispose of emergency supplies after the debacle of 1934: in February civil war briefly broke out between the Socialists and government forces. As a result the Socialist party was outlawed and material that could have incriminated its members had to be destroyed... My helpers were Steffi and Hans Kunke. I became friends with Steffi. She was a teacher and a great person: carefree, cheerful, open-minded. Her large, sparkling eyes spoke such a clear language of affection and enthusiasm.”[*] Helen Potetz, a Ravensbrück survivor who met Steffi there remembers her as “the ray of hope that gave everyone lots of strength.” She also talks about Stephanie’s talent in composing poems and telling fairytales that unfortunately mostly were not preserved – when Rosa Jochmann, the leader of her block, was arrested in 1943, all papers were destroyed.[*]

The letters that Steffi wrote to her aunt Flora Jelinek are filled with this mixture of cheerfulness and bitter wisdom at the same time. Her letters convey the piercing emotion of a condemned person who still could gain joy from just being alive by observing the clouds, the sun, and the mountains in the far. Her language is delicate and poetic, and the images are especially distinct and tangible:

Because of the blackouts we go to bed early. But I lay in bed for a long time, and think and muse. I am a night owl and need less sleep.

The best thing for us here is the sky, it is so beautiful. It is not as high as in Lichtenburg. Since the barracks are low and long, the whole camp makes an impression of being low and wide, and because of that the sky here is very low... We have wonderful sunsets here, the colors are so beautiful ...

These shines are unforgettable, so clear, so dear. I often have this feeling when experiencing physical inconveniences, I feel happy in this flood of light.[*]

Steffi managed to stay within the limits of the camp correspondence and at the same time to express something that goes beyond censorship. Even the dangerously self-humorous remark reaches the addressee untouched: “Well ... I can find some beautifulness and fortune even in the wretched life.” By the end of her imprisonment in Ravensbrück, her mood changes, and the letters bear the traces of tiredness that Steffi’s comrade also remembers: “she would always tell us that she will never leave the camp alive ... She had a weak heart and no will to live anymore.” In the last letter of our collection, dated from December 1941, probably foreseeing her deportation to Auschwitz, Steffi writes to her aunt:

The time goes overwhelmingly fast, and at times I wonder where all those weeks are gone. When sometimes I imagine myself living as a “private” again this seems to me as real as the fulfillment of a fairytale. And what does remain? I know, my dearest, that if I could live my life once more, then it would have been already wonderful. And while I just know that sometimes I doubt the possibility of its fulfillment.[*]

In the beginning of 1942, Steffi was commissioned, along with other comrades to go to Auschwitz. Release from the transport was impossible, and Steffi also did not want to let her friends down. About what happened in Auschwitz we find out from Potetz’s testimony:

This was a tough farewell for all of us... From the friends that came back from Auschwitz we found out that she got sick with typhus, and never recovered ... The live will of those that spent time in the Strafblocks and led a miserable existence in Auschwitz was broken. Sometimes she suffered from the nameless homesickness, and her last days and hours were spent dreaming about Vienna and being at home.[*]

One of Vienna’s streets was named Kunkegasse, as a tribute to Stephanie and Hans.

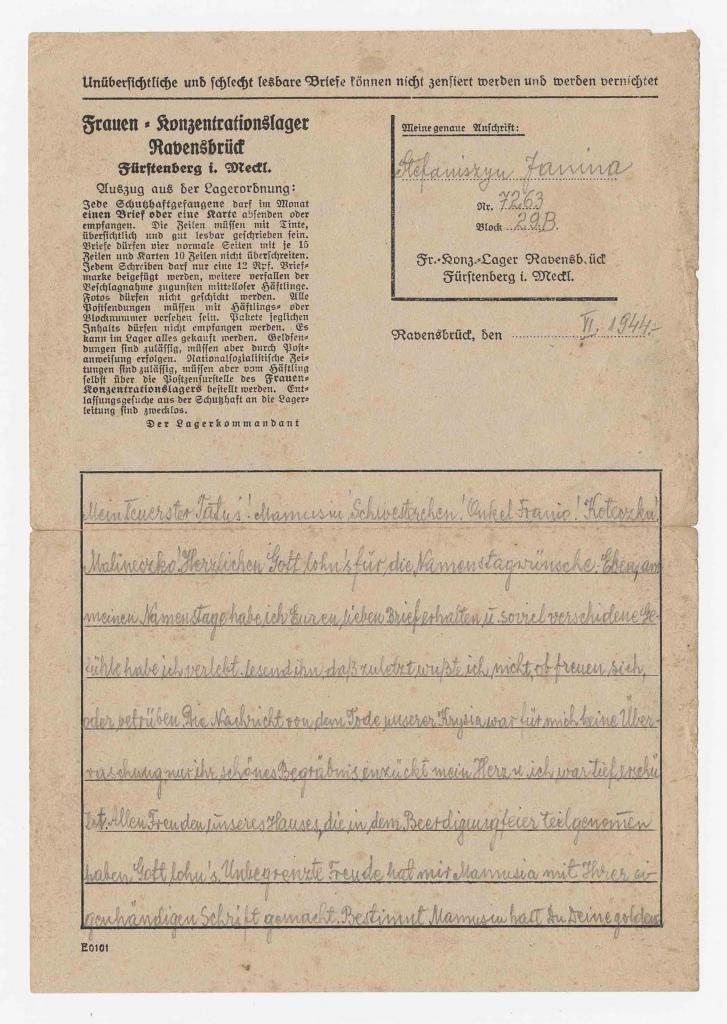

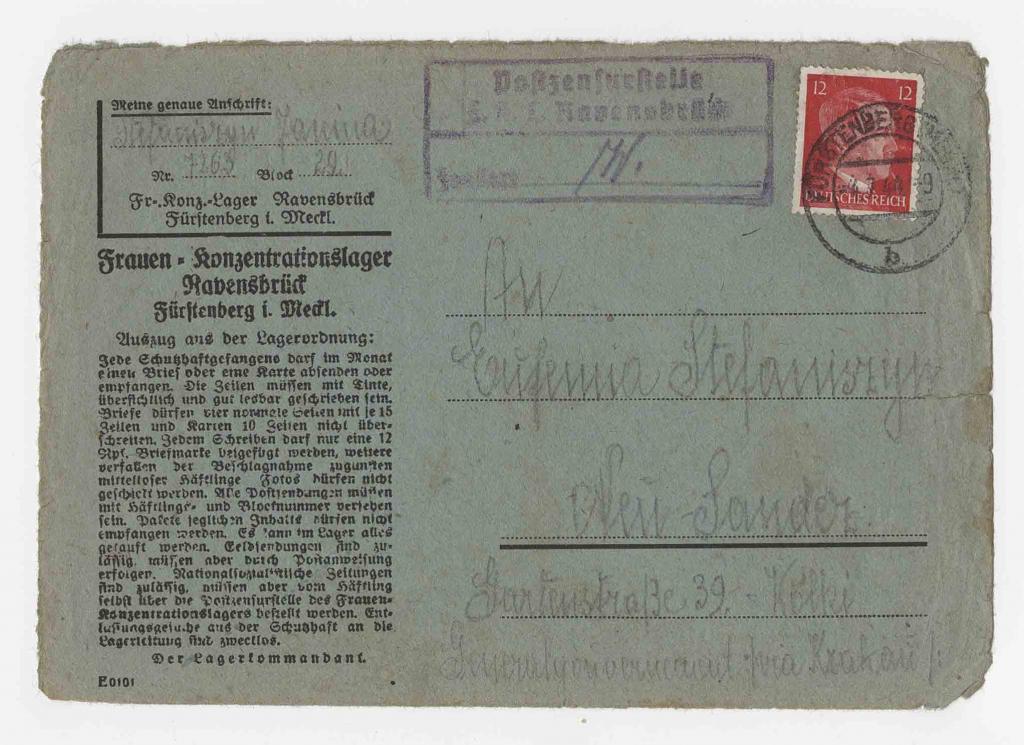

Another set of correspondence belongs to the Stefaniszyn sisters, also prisoners of Ravensbrück. After Germany invaded Poland, Jozefa and Janina, Polish scouts and activists (Janina was a lawyer, and Jozefa was a teacher) joined the underground resistance. Both of them worked at the legal firm Sichrawów that served as a cover for covert activities and in reality was busy delivering information about the victims that were shot in the streets to their families. According to the recollections of Joseph Bieniek, “Janina wrote the letters informing families about the fate of those dear to them, while Jozefa dealt with the shipment.” With the spread of rumour among local families, the Sichrawów firm started to be frequently visited by Polish women frantically searching for news about their loved ones. Eventually, one of the associates was arrested and, being unable to endure torture, gave out the name of the firm. As a result, the company chief, and then the Stefaniszyn sisters were arrested in spring 1941 and deported to concentration camps.[*]

Concentration camp. Get out. We were packed into the truck, almost without air - you could suffocate. The gate of the camp. The Dogs are revolving around us and barking furiously. Gestapo - men in black cloaks, with evil faces, burning with a vengeance. This is all hell, hell here, hell on earth ... Search, a bath, we are now dressed in prison stripes, receive wooden shoes, hair shaved, beating, kicking.[*]

When we arrived to Ravensbrück we saw a huge camp, with the gas chamber, with the smoke. And everybody looked alike, with the shaved heads. As they marched us we saw corpses by the side of the road.[*]

In Ravensbrück, Janina and Jozefa joined the Polish underground organization Mury (“The Walls”). This resistance movement, established in November 1941 by the scout leader Jozefa Kantor, was mainly “organizing food and medical supplies for the sick fellow prisoners, moral, psychological and religious support for the group members and other women in the concentration camp.” Being not numerous in the beginning, by the end of the war it reckoned about 100 Polish women. The members of the “Walls” managed to fulfill the priceless task of preserving the “incoming list” of 25,028 Ravensbrück prisoners, since the rest of camp documents was destroyed by the fleeing SS personnel to conceal the evidence.[*] In 1945, Janina and Jozefa were rescued – they went to Sweden with the transport organized by the Red Cross and Count Bernadotte. After the war, the sisters returned to Poland, and received various awards, including The Knight's Cross of the Order of Rebirth of Poland and The Golden Cross of Merit of Poland.[*] Jozefa returned to her teacher’s duties, and on the memorial website dedicated to the history of Mury she talks about the occurrence in her pedagogical practice that illustrates the impact that the survivors endured as a result of their horrible experience:

When I hear German music and songs on the radio, I am always wondering about this nation’s supposed love of music. Even the SS liked to sing, and yet they were capable of such crimes. How can one be reconciled with these things? The one that loves music is a good and honest person, and cannot cause any harm; and yet we have such criminals in this case. I do not understand that anymore. <...> Let me give you an example of how I once reacted when one young boy sang the German song “Heili, heilo” (he got that melody from the movie). At first, I grabbed the brat by the ear, but then I restrained myself and gave them one-hour lecture. <...> I pointed out that with this song our parents were being shot. I took them to the nearest place of executions, told them that I was an eyewitness to shooting near my home. Finally, I added: Will that be nice to each of you, to have someone executed in the family, like father or mother, and then listen to the tune, with which the executions were carried out?[*]

The four letters (three from Jozefa and one from Janina) kept at the archive constitute a part of a bigger correspondence. While obeying the rules of camp correspondence and speaking only about general things, the sisters are still able to personalize their writings, to add some genuine sentiment. Both of them are deeply religious, and this emotion dominates Jozefa’s letters:

Today is Sunday! I am now musing on different things about my life, and trying to find a source of joy. Finally, I have found that! Oh my quiet church! I know all your corners so well. How often have I visited you… Oh my beloved daddy! Oh! My dearest, if only I could go there with you and to sing my favourite song. The rustling acacia quietly sings this song in God’s care. “Oh, the God almighty.” I have sung that often, and I did not realize then how happy I was![*]

Being separated from their family, Jozefa and Janina were strongly supported by their Christian faith and kept their rituals and prayers even in the conditions of a concentration camp. When greeting their loved ones at Christmas, Jozefa writes, and this gets through censorship: “On Christmas Holiday Jasia and I spent with you. On Holy Night, when the first star lit up, we sang the beautiful Christmas songs very loudly so that you could hear us. It seemed to me that Baby Jesus stretched his hands to us and said: “Come, you the sad ones, and I will sooth you!”[*] After the war, in a testimony dedicated to the icon of Mother of Consolation, Janina also wrote about the secret sermons carried out at their block and how morally supportive they were for the prisoners:

Longing for the church and Holy Communion was the heart of our second camp, which carved our souls, ennobled, and led us to our Consolation... The Mother of Consolation knew prisoners from many cities, from Vilnius, Poznan, Gdansk, Sopot, Plock, Radom, Czestochowa, Krakow, Tarnow... You were with us at the moment of suffering and joy, you heard at the catacombs of our camp songs sung to Thy honor, these common prayers that gave us strength to survive the tough leaden days of camp... The block in which we lived was dedicated to the Sacred Heart of Jesus... Selection ... execution ... these things explicitly bypassed us... No hunger, no flogging, no anguish, if faith is strong in us, if the Mother of Consolation is with us. Prayer and work, and we nourish ourselves happy and content.[*]

As in case of other prisoners, the majority of Jozefa’s letters are dedicated to her and Janina’s homesickness, but as opposed to male writers, she finds it possible to be more specific, sometimes speaking about the real life of a prisoner, even when confirming the arrival of a food package:

Greatest thanks for such wonderful packages. I have received three, and Jasia also three packages with food. First of all I kissed the bread… All my comrades wept loudly, when they saw my love to you. <..>[*]

Though the handwriting of both sisters looks very similar and perhaps only one of them could write German (or that someone wrote those letters for them), Janina demonstrates a different style, and keeps to a less passionate manner. She asks questions about common friends and relatives, addresses different people and even asks her parents to let some acquaintance know that she is unreachable because of being in the camp. Janina also gives little insights into their life in camp and even mentions the woman who supposedly was mentoring and helping them in Ravensbrück:

The elderly lady that was so wonderful to congratulate our Jozja <Jozefa> on her name day, is thanking you for the money; she is very happy. She treats us as her own daughters.[*]

In one of the VHA interviews, a Jewish survivor of Ravensbrück remembers how she and another girl prayed during the Yom Kippur Holiday, and then adds that in the camp they were “reduced to animals thinking only about food... No favours existed in Ravensbrück. Only few of us still did that, to remain human.”[*] The examples of the Ravensbrück correspondents, such as Steffi Kunke or the Stefaniszyn sisters show how the very act of writing helped them to preserve their faith, their cheerfulness and stoutness in the conditions of imprisonment. The emotional capability to get their personal messages through the grind of the SS censorship grants us the possibility to look into the very core of humanity.

NOTES

[1] Lørdahl, Erik. German concentration camps, 1933-1945: history and inmate mail. Vol 1. 91-92

[2] Morrison, Jack G. Ravensbrück: Everyday Life in a Women’s Concentration Camp 1939-1945. Princeton: Markus Wiener Publishers, 2000, 309

[3] Vansant, Jacqueline, Reclaiming Heimat: trauma and mourning in memoirs by Jewish Austrian reémigrés. Wayne State University Press, 2001, 77

[4] Buchenwald concentration camp, 1937-1945: a guide to the permanent historical exhibition by Harry Stein, Gedenkstätte Buchenwald. Wallstein Verlag, 2004-01-01. p. 300

[5] Vansant, Jacqueline, Reclaiming Heimat: trauma and mourning in memoirs by Jewish Austrian reémigrés. Wayne State University Press, 2001, 77

[6] Helene Potetz, “Die Haft von Stefanie Kunke.” (The imprisonment of Stefanie Kunke) In: Gerda Szepansky, Helga Schwarz ...und dennoch blühten Blumen: Dokumente, Berichte, Gedichte und Zeichnungen vom Lageralltag 1939-1945. Brandenburgische Landeszentrale f. politische Bildung (Oktober 2000). 59-60

[7] Helene Potetz, “Die Haft von Stefanie Kunke.” In: Gerda Szepansky, Helga Schwarz ...und dennoch blühten Blumen: Dokumente, Berichte, Gedichte und Zeichnungen vom Lageralltag 1939-1945. Brandenburgische Landeszentrale f. politische Bildung (Oktober 2000). 59-60

[8] These letters, written in purple pencil on brown paper shreds, survived the war and when the sisters returned from the camp I visited them - scraps of faded, I read with considerable emotion. Especially the final postscript: "Send immediately notices to the families." Józef Bieniek, Lord Znad Dunajca, http://www.nsi.pl/almanach/art-ludzie/lord_znad_dunajca.htm

[9] Almalech, Bella, Interview 35621, Visual History Archive. USC Shoah Foundation Institute. 2012. Web. 15 Feb. 2012

[10] Taube, Yehudit, Interview 6313, Visual History Archive. USC Shoah Foundation Institute. 2012. Web. 15 Feb. 2012

.jpg)

.jpg)