The Jewish Scouts organization (in French, Les Éclaireurs Israèlites de France, EIF) was founded in 1923 by Robert Gamzon in France. First based in Paris, the EIF headquarters were later moved to Moissac, a small town in the Midi-Pyrénées region of Southern France. When the war started, this movement was already well-structured, with its leaders and activities, and therefore ready for the hardship of war and occupation. Lucien Lazare, a historian and a former resistance combatant thus describes the role of the EIF in occupied France:

The first to regroup and go into action in the southern zone, the EIF provided a framework in which both native French Jews and immigrants had experienced an integrated community since the 1930s. Involved in all forms during the war except political indoctrination – education, culture, publication, religion, mutual social assistance, professional retraining, clandestine rescue, and armed combat – they were active in Paris and throughout the southern zone.[*]

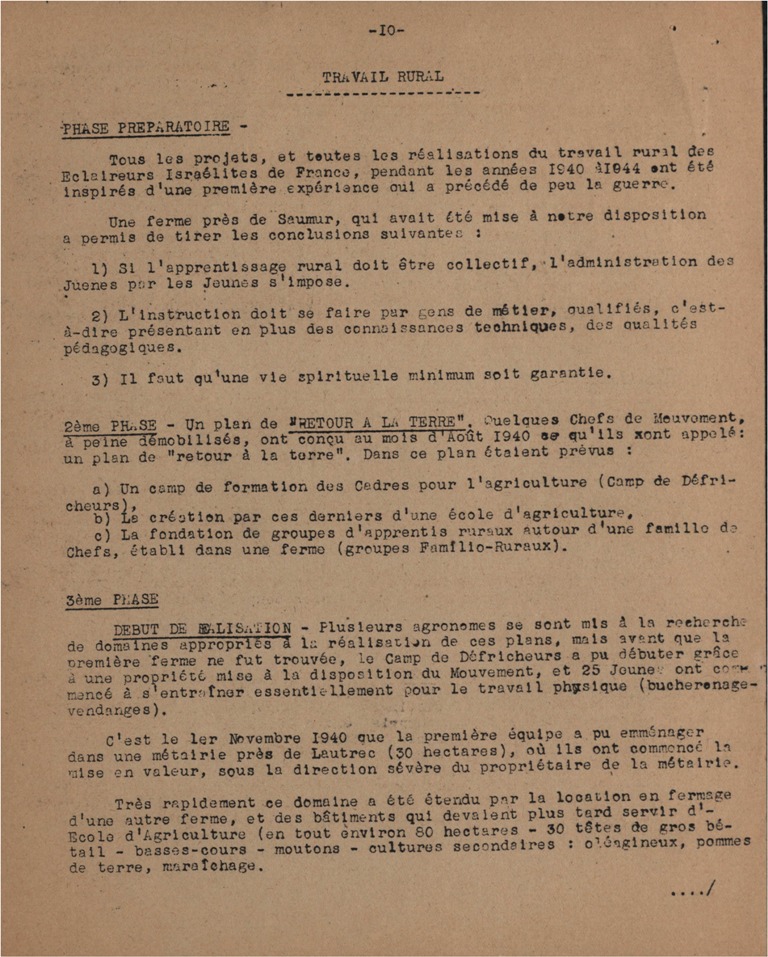

The EIF moved in several directions of accommodating the Jewish youth before and during the war. The main activity that they were preoccupied with was the “back to earth” movement. The leaders of the scouts encouraged the Jewish urban youth to go to the farms and start their new life as peasants and farmers. After Nazi Germany occupied France farming received an essential value of, first, taking care of the food shortage, especially for people in hiding, and second, supplying the kids with the practical professions. This is how the EIF report describes the process of establishing the first community in the small holding near Lautrec (30 hectares):

It was on this property that the team did the first rural apprenticeship, and at the same time perfected their spiritual formation. It was in this domain that the most important and difficult work was to be done. This meant that young people who came out of the war all grown up, some twenty years or older, already had their character formed.

After a year of work in a commune groups, youth had the choice to detach themselves from the group to take charge of our first autonomous farm. A farm of 60 hectares and contrary to the soil in Lautrec, this farm's soil is in a good state.

Those who were left after the pioneering of the farm were placed with other farmers in the area.[*]

Despite the lack of experience, these newly organized farms were functioning successfully: by 1942, to the utter surprise of the local peasants, “the [scouts’] population was stable, the equipment was satisfactory both in tools and in livestock, and production was respectable from land that had to be cleared and often of poor quality. Most of the young people had overcome the difficulties of a regime of rigorous physical labor that was like nothing they had previously experienced.”[*] Besides the EIF farms, there were a number of purely Zionist farms, called the Hakhsharot (“preparations” in Hebrew) all over France. According to Anny Levy, the Hakhsharot were created to gather the youth together, and inspire them to become Zionists. “Partly the goal was matchmaking, so that you could go to the kibbutz together. There were not many unmarried people in kibbutzim at that time. You would learn Hebrew, the basics of Zionist, and you would learn how to farm."[*]

While the EIF was neither religious nor Zionist by its nature, the very idea of sending the young Jewish people to the countryside was similar to the Chalutzim ideals, the pioneers that went to Eretz Israel. Michael Taylor says that after he fled to the Southern part of France the Jewish resistance placed him in the farm run by the EIF, where he spent about six months:We lived together, took care of cows. We had Saturdays, kept kosher, had Sabbaths. In 1943, the situation got worse, French gendarmes kept looking for us but they did not know which farm we were in.[*]

By 1943, the danger of deportation and death became so imminent that despite the farms’ success the leaders of the EIF decided to have them dispersed. In November 1943 the workforce on the farms was decreased to a minimum, given also the fact that the weather that year was “disastrous for all agriculture in the south of France.” The farms kept working and producing low amounts of food till 1943, when the Germans occupied the southern zone. Now the people were more involved in the individual placements for those with false papers, voyages to Switzerland and Spain etc.:

At that moment the danger was really inevitable. The power of the French police and the police stations were practically handed over to the militia and the Gestapo. The responsibility of our leaders became too great and the work had to be stopped. The hard decision was made to dissolve all of our centers and material possessions, even livestock; we had to go into hiding.

The document concludes with the promise to continue the development of the farms after the liberation, with the final goal of either bringing the farming to the soil of Palestine or staying in France as a “Rural Jewish enterprise.”

In addition to the rural groups, the EIF also organized centers of education that were specialized in providing the professional training for children and teenagers. Henri Masliah, aged 17, was told by someone in Paris to cross the demarcation line and go to the southern zone, to the EIF headquarters in Moissac. He was placed with other kids, from the age of 7 to 18: “We had courses in metallurgy, carpentry, electricity, and book-binding. I went to the electricity classes. We were educated by the professors from Europe who were over-qualified. I had a professor of mathematics who lost his job because he was Jewish <…> It was a very good atmosphere.”[*]

He lived and studied there for a year, met his future wife, and most of his dearest friends are from this group. Masliah says that the kids lived in the great atmosphere, with some elements of Jewish tradition: “We kept a Shabbat, learnt Hebrew, sang Jewish songs, and this was a feeling of a very good community."The goal of the EIF movement was not only to hide and accommodate children but to offer them the opportunity of receiving the practical skills (such as farming or metallurgy):

The children go to workshops in the morning, whereas the afternoon is reserved for general formation. Hebrew and Jewish history are equally important parts of our education in the schools. Every semester a report card is done by the teachers to the students in the house. There are board meetings every three months with teachers and students to discuss matters on their classes and workshops. [*]

In 1943, the Nazis occupied the Free Zone, and staying in Moissac became too dangerous. The children were given false IDs, and sent to different parts of the country. Some went to the farms, some entered the schools, and some went into the mountains. Masliah went to “Marmonde, which was 50 kilometres from Moissac, where I entered a boarding school. The principal was waiting for us, and right away instructed us what to do if the Germans would come. He knew that we are the Jews in hiding.”

The EIF went underground, with its participants starting to be involved in sabotage and military operations thus joining the general resistance. The rural groups still existed in hiding, thus in Lautrec the farm was guarded “to ensure the safety of our youth against Gestapo attacks. The training continued in different regions, this time, concentrating on the “physical and military training.” They also recruited boys and young men from the local non-Jewish population, and they “considered joining the Lamaquiere and fight it during the mobilization.” Another group, based in Sarrie, was more oriented towards Judaism: they observed Shabbat. From the EIF, the Lamaquiere recruited people, and became the only group to be armed in the given region. According to Henri Masliah who joined them after the D-Day, the group mostly consisted of the Jewish refugees from Poland, Germany, and other countries, while the French Jews were in minority.

The EIF document describes one incident when the Jewish Scouts were first attacked by the Germans, and then were able to capture the military train. This happened soon after the Allies’ landing in Normandy when the south of France was still occupied by the Germans. Michael Taylor remembers that the EIF found out that there will be a train full of German ammunition and weapons passing near the place where they were hiding. The plan has been made to attack it, with the help of American parachutists that were helping partisans. The mines were put under the tracks, and the first couple of cars were blown off the railway tracks:

A veritable battle began between the canons on the train and our American machine guns. Around midnight the fighting had slowed down, we had used most of our ammunition, but our boys had killed almost everyone who was carrying guns; and we resumed our bombardment of the train with our mortars. After experiencing heavy losses the German captain raised the white flag and surrendered himself, 56 men and all the contents of the train to Lieutenant Roger.

For the Jewish resistance, it was extremely important to emphasize the fact that they were the Jewish fighters. Taylor recounts how he came up to one of their captives and asked him “Do you know who I am?” The soldier answered – yes, you are a partisan. - No, said I, I am stronger than that. “Ich bin ein Jude.” Well, he was wearing a green uniform but his face was much greener when he heard that. He was terribly scared. I told him that I was not the only Jew, that they were surrounded by them.”[*]

Another resistance fighter says that when he noticed a German out of the corner of his eye fiddling with a hand grenade, he ran up to him grabbed him off the train and started beating him crying out “This is what a Jew can do to you.”[*]After that, the partisan unit took the ammunition and headed for Castres:

The automatic weapons were re-usable and we mounted them on our trucks transforming them into tanks. By consequence we created an attack for the garrison at Castres; we would go along the road making defensive stations along the way. We learned from intelligence services that for from wanting to attack us, they wanted to enter into negotiations with us. The commander left alone and arrived in Castres, while to company surrounded the city blocking all exits. The next morning 3500 men surrendered to 250 men from the underground.

According to the former resistance fighters, the Allies entered Castres three days after this victory; and the liberation of this town has been achieved by this unit alone. Once in Castres their captain demanded that the German Commandant surrender himself and his troops. Coincidently the city had been bombarded just a few weeks earlier and the Captain of the resistance explained if they did not surrender they would die. The German Commandant surrendered 4000 German troops to 350 underground troops. Jacques Weltmann remarks that once they had secured the town, all of a sudden the French army who had done nothing was all over the town, there were lieutenants, captains and generals. The general consensus between the resistance fighters was that the French army could in his words “go to hell”.

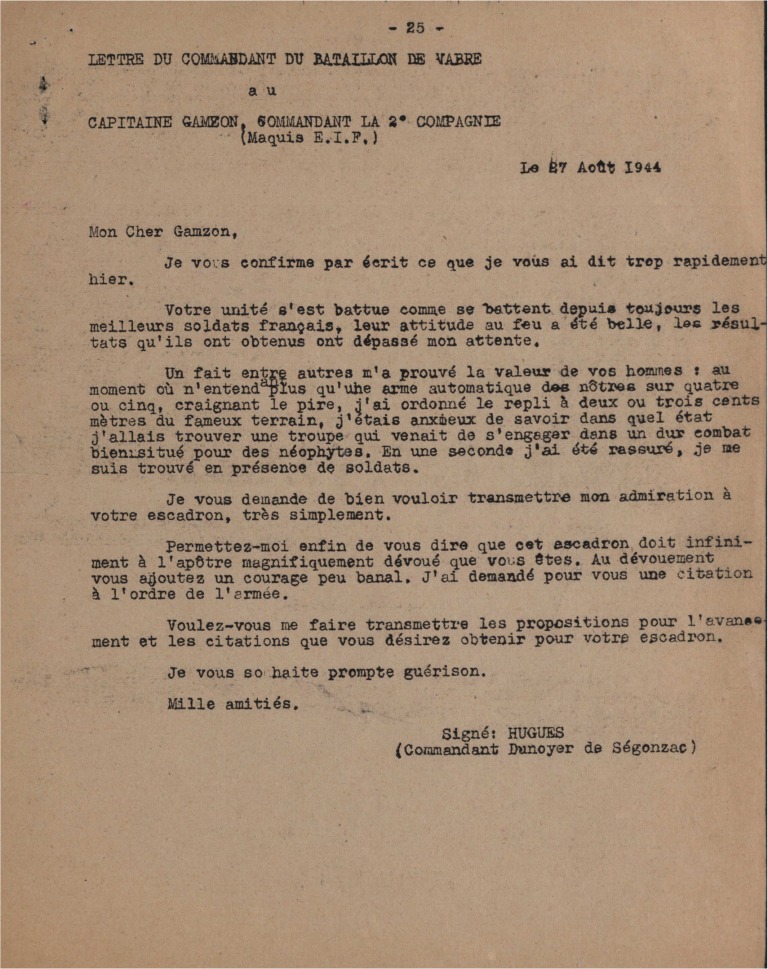

This extraordinary event was followed by a letter sent by the commander of Dunoyer de Segonzac addressing Gamzon, who was severely wounded:

Your unit fought a good fight and like always proved to be the best French soldiers. Their attitudes in the middle of fire were beautiful and the results they produced far exceeded my expectations. <…>

I ask you to please extend my feeling of admiration to your squadron.

Let me finally say that your squadron is just as dedicated as you are [he likens their dedication to apostles]. To your devotion you had a sense of courage that is not commonly seen. I have asked on your behalf for a military citation.

Regarded as a heart of the Jewish resistance in France, the EIF was indeed unique, in terms of the scope of their actions. The town of Moissac constituted the safe haven for a while, where the Jewish youth could find their place to live and not to starve. Every activity that the organization was engaged in was expanded to accommodate even more needs of the persecuted people. They hid the children – and gave them education. They taught Judaism and observed some holidays – and also provided the young people with the professional education. They sabotaged the German trucks and trains – and participated in the real battle.

Robert Gamzon survived the war, moved in 1949 to Israel, published the memoirs, and died in 1961.

NOTES

[1] Lazare, Lucien, Rescue as Resistance: How Jewish Organizations Fought the Holocaust in France. New York: Columbia University Press, 1996, 54

[2] 0182 Rapport sur l’activité du mouvement des Éclaireurs Israélites de France de 1939 au lendemain de la Libération [undated]

[3] Lazare, 60

[4] Levy, Anny, Interview 24669, Visual History Archive. USC Shoah Foundation Institute. 2013. Web. 15 March 2013

[5] Taylor, Michael, Interview 19695, Visual History Archive. USC Shoah Foundation Institute. 2013. Web. 15 April 2013

[6] Masliah, Henri, Interview 18738, Visual History Archive. USC Shoah Foundation Institute. 2013. Web. 15 April 2013

[7] 0182 Rapport sur l’activité du mouvement des Éclaireurs Israélites de France de 1939 au lendemain de la Libération [undated]

[8] Weltmann, Jacques, Interview 29863, Visual History Archive. USC Shoah Foundation Institute. 2013. Web. 15 March 2013